We talk to people all the time about Dolt and what they want to use it for. We recently started calling Dolt “The Database for AI” because we think Artificial Intelligence (AI) needs version control for a number of reasons. Dolt is the only database with true Git-style version control.

We hear from people who want to use Dolt as a feature store for their training data or to build Cursor for Everything. We hear from people who think Dolt will be a good database to back their App Builder apps. As evidenced by the linked blog articles, we understand these use cases pretty well.

The AI use case that surprised us was that people want to use Dolt for “agentic memory”. What is agentic memory? How can Dolt help solve the agentic memory problem? This article explains.

How Agents Work#

To understand agentic memory, you first have to understand the basics of how agents work. The most successful agents are coding agents, but the same principles apply to any other agent.

Context#

The fundamental building block of AI systems is the Large Language Model (LLM). The input to an LLM is called context. The context includes a user-provided prompt and any additional information the system calling the LLM adds. The user and system information together is called the context.

Context is very important for LLMs to give the correct answer. LLMs focus on information in context using a process called attention. Attention is such a fundamental concept in LLMs that the paper credited with inventing LLMs is called “Attention is All You Need”.

Andrej Karpathy thinks working with LLMs should be called “context engineering” instead of “prompt engineering.

As Karpathy notes, too much or too little context can degrade the performance of an LLM, causing incorrect answers. Creating the right context is one of the major differentiators in agent performance. Good agents produce good context.

Looping#

Looping and tools are what makes an agent an agent. Producing a single context and sending it to an LLM is not an agent. Agents are defined by their looping and tool use according to Anthropic.

Agents can handle sophisticated tasks, but their implementation is often straightforward. They are typically just LLMs using tools based on environmental feedback in a loop.

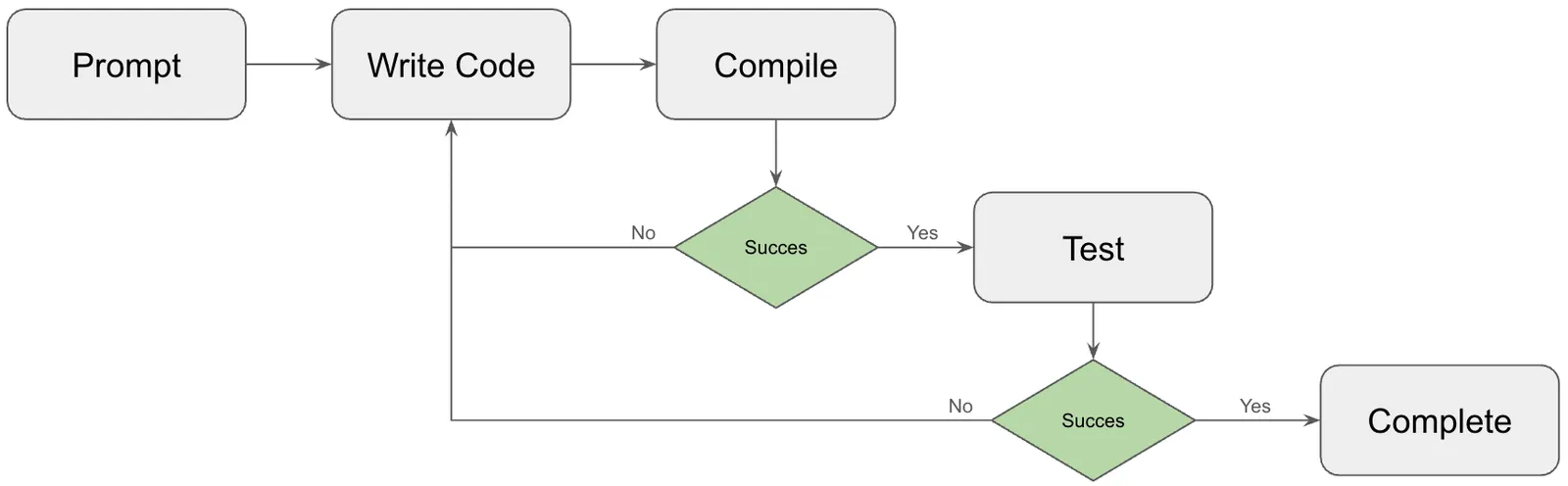

We’ll cover tools in the next section, but looping is pretty easy to understand. The agent has a goal established from a user prompt. Coding agents use context to produce code and iterate until all verification gates are passed. Does the code compile? Do tests pass? If not, augment the context and change the code until it does. The more layers of verification, the better the coding agent performs. Code has a number of built-in verification steps, which is why coding agents work so well compared with agents in other domains.

Tools#

Tools are actions an agent can take. Some examples of coding agent tools are read from a file, write to a file, and use the terminal. When you watch a coding agent, you will see the agent using a number of tools to get tasks done, only interrupted by moments of “thinking” where the agent is assembling context, sending it to an LLM, and waiting for a response.

You can also define custom tools using Model Context Protocol (MCP). MCP creates a pluggable tool ecosystem for agents to work with non-standard or proprietary systems. The MCP tools available are automatically added to context so the agents pay attention to them.

The Problem#

As mentioned, the most successful, widely-deployed agents are coding agents. Coding agents are amazing, time-saving tools. However, as software engineers have used coding agents over the past six to nine months, some problems have become obvious.

Cold Start#

Every Claude Code session starts as a blank page. Steve Yegge, a thought leader in the agentic memory space, describes the problem with typical Steve flourish in the Beads launch blog article. Beads will come up later.

The problem we all face with coding agents is that they have no memory between sessions — sessions that only last about ten minutes. It’s the movie Memento in real life, or Fifty First Dates.

Surely the solution to the cold start problem is “agentic memory”? Let’s just store the context and retrieve it when needed. Most agents allow you to resume a session. Is that not a first pass solution to agentic memory?

Context is Limited#

Unfortunately, the size of context is limited both algorithmically and practically, so whatever agentic memory solution you design must fit with the context limits of the LLM.

LLMs advertise a context size limit. Gemini 2.5 Pro allows for 1M tokens of context. Claude Opus 4.5 allows for 200k tokens of context. Chat GPT-4o allows for 128k tokens of context. This size limit is an algorithmic limit according to Jeff Dean, an early pioneer in almost everything Google. This is how he describe the context limit on the Dwarkesh Podcast.

But [unlimited context is] going to be a big computational challenge because the naive attention algorithm is quadratic. You can barely make it work on a fair bit of hardware for millions of tokens, but there’s no hope of making that just naively go to trillions of tokens.

Making matters worse, even if we solved the algorithmic problem, LLM answers degrade with too much context, a phenomenon called Context Rot. The LLM “attends” (ie. pays attention) to information in context. The more information in context, the more likely contradictory pieces of information exist and irrelevant information is included. This causes LLM performance to measurably degrade with the number of tokens in context.

So agentic memory must not only solve the cold start problem but also store and retrieve only the context that matters for the task at hand.

Can’t Do Larger Tasks#

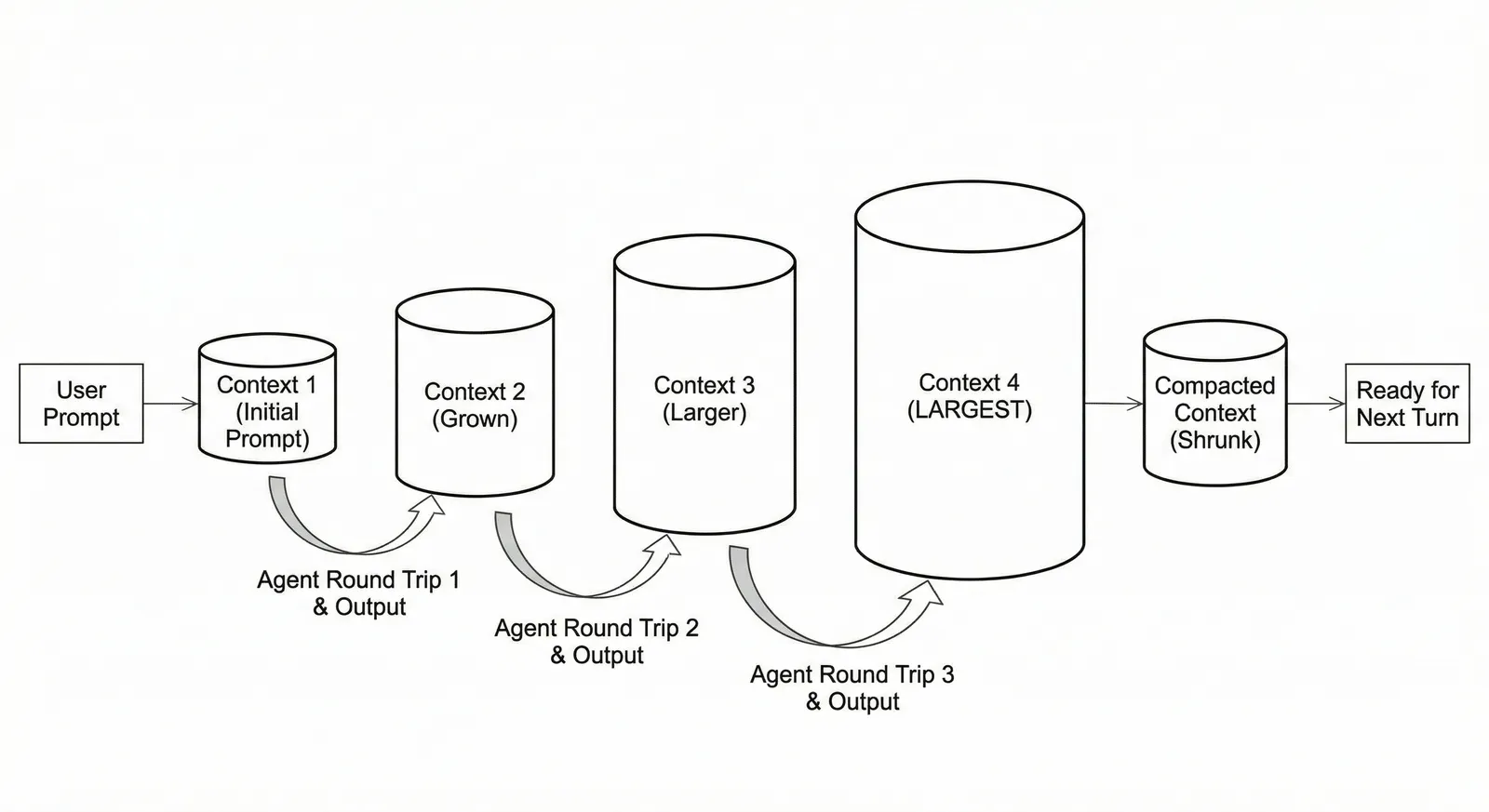

To get around context limits, coding agents implement “context compaction”. When the coding agent nears the context limit of the model it is using, it compresses the previous context down to a summary and starts a new session with that summary as its new context. This event can either be a godsend if your session has gone off the rails or it can send your session off the rails. Most modern agents go into “finish now” mode before context compaction, knowing what happens after is a roll of the dice.

What this context limit means is that agents are not very good at accomplishing larger tasks. Most skilled agentic software engineers are very good at breaking a larger problem down into tasks they are pretty certain a coding agent can pull off. They then sequence these tasks manually through a number of individual coding agent sessions.

The promise of agentic memory is that agents would better weather the context compaction phase and potentially break down, organize, and execute larger tasks much like humans do.

Multi-Agent#

With current agents limited to short lived tasks, there is not much use in deploying multiple agents on a single task. However, if an agent can break down, organize, and execute larger, complex tasks using agentic memory, this unlocks multi-agent use cases. Instead of having a single agent execute tasks sequentially, many agents can execute tasks in parallel to reach a larger goal. Necessarily, this requires shared agentic memory with each agent updating and reading memory concurrently.

Agentic Memory#

So what context should be kept around to allow agents to perform work reliably over multiple sessions? This context should be limited to only relevant information for better LLM performance. The context kept around between sessions is agentic memory.

Context as Stack Trace#

Let’s just store all the context!

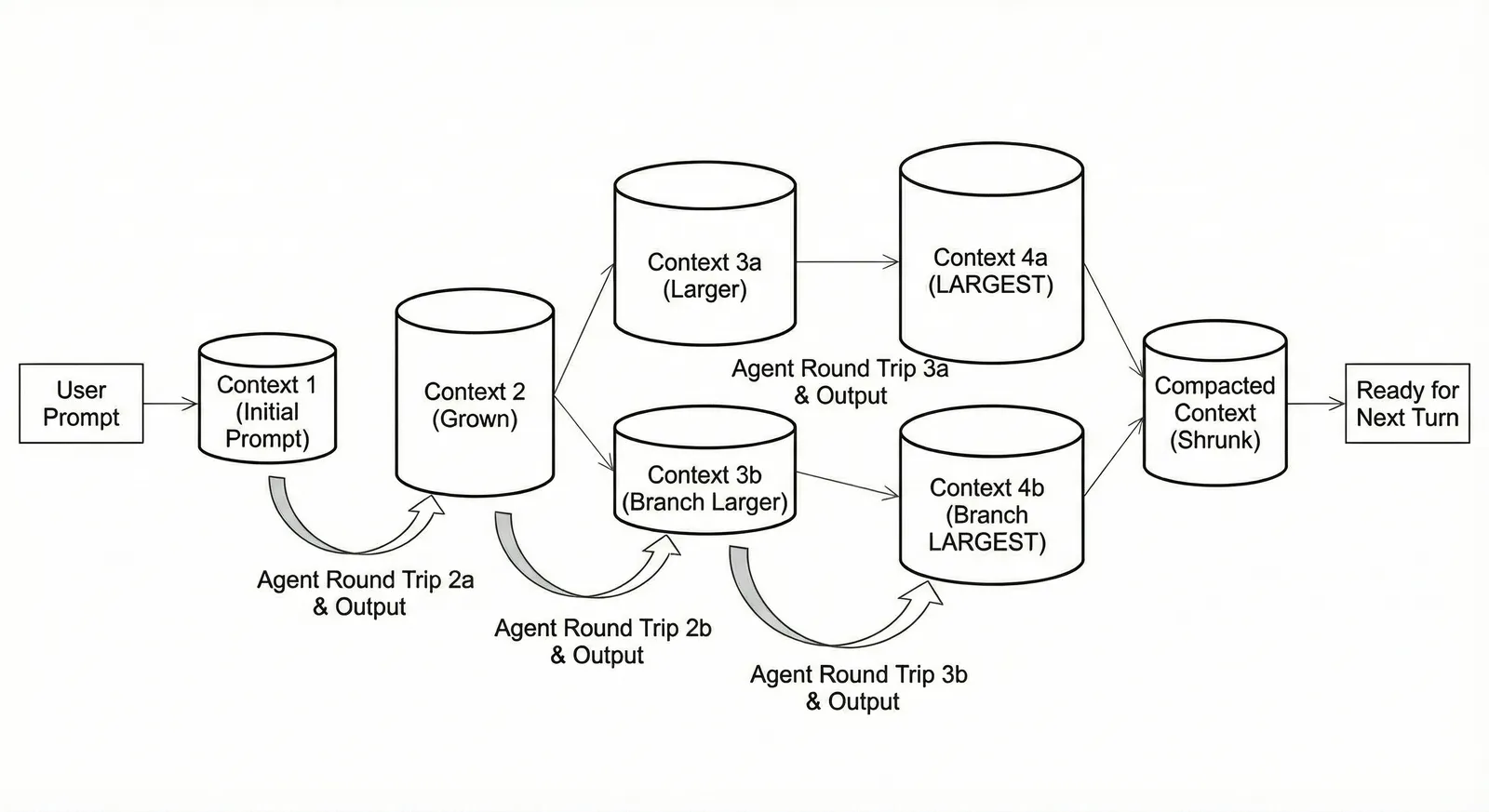

A naive agentic memory model is to store all context state out-of-band in external storage. This system would start empty and grow as the agent works, simply adding the context sent in each LLM call to a storage system. Compaction would shrink context, not memory. Memory is sitting in storage instead of polluting context. This would resemble a context stack trace. This is a linear memory model. This model is that it is simple and easy to understand.

This agentic memory system would allow you to “rewind” an agent session to an earlier state. The agent went off the rails after it looked at this file. Rewind to that point and instruct the agent to do something different. Context differences, diffs, could be exposed to users and agents to help debug what happened.

An agentic memory system like this could expose rewind, diff, and other memory recall as tools to the agent. The key problem is what pieces of context to expose. How does the agent know what to recall from memory? Pulling in all context from an earlier state is likely to overload context. This gets to the fundamental questions of agentic memory. What pieces of context are important to remember? What pieces of context are fine to forget?

Non-linear Context#

A more complex memory model is non-linear. What if agentic memory was a graph of context, with branches and merges, much like we have in version control? An agent could try three ideas at once and merge the best solution. This post captures the vision.

This agentic memory system provides rewind, diffs, branch, merge, and many other version control-style features that an operator or the agents themselves can use as tools. However, this system still runs into the same problem as the linear agentic memory system. What pieces of context are important to remember, and what pieces of context are fine to forget?

What Should Agents Remember?#

What pieces of context should agents remember? This is currently an open question. But, over the past couple months, there’s been some innovation.

All Context?#

This is where agentic memory approaches started. As noted above, storing all context suffers from context limit problems, but it does provide an agent useful rewind and diff capabilities if stored linearly. If a context graph model was adopted, agents could branch and merge context. These features could be useful in a multi-agent world where multiple agents were operating on branches of context.

I don’t think saving all context is the shape an agentic memory solution will take in the long run. However, saving all context is simple and cheap. Historical context provides useful features, even if just for debugging. One of the gating factors to this approach with current agents is that context engineering is one of the differentiators between different agents. So, in most agents, context is not readily available.

Tasks?#

This is where we start to see some agentic memory innovation. Steve Yegge, who was mentioned earlier, had a profound insight when trying to build a multi-agent system. Agents worked better, for longer, if they offloaded task management to a separate system. He implemented an agentic memory system called Beads that stores tasks.

We’ve tested Beads, and indeed, agents can work uninterrupted for hours when instructed to use Beads for task management. We’ve only been using Beads for a week, and the longest session we’ve observed is twelve hours, where useful work was produced at the end. Raw coding agent sessions max out at about an hour. Using Beads with an agent is an order of magnitude improvement.

Beads has interesting design considerations for agentic memory. Tasks are hidden from context until the agent needs them. Agents can read, create, and update tasks. Task data is structured to provide clear relationships that raw text cannot model. Tasks are version-controlled so an agent can see what has changed if something goes wrong.

Something Else?#

If managing tasks external to an agent in a version-controlled fashion helps the agent work better for longer, are there other pieces of context that would exhibit the same pattern? I would guess the answer to this question is yes, and I suspect it will become an active area of research soon. Any piece of context that can be offloaded to reduce cognitive load on the LLM is probably a good candidate for a Beads-style approach.

How Should Agents Remember?#

So if offloading context into agentic memory has proven effective, what is the best way to store and recall this context? Beads suggests the essential element: version control on structured data.

Version Control#

A hint to how agents should remember may lie in a system agents already used effectively to manage context. Agents use version control very effectively to remember and manage code changes during a session. Moreover, the agentic memory features we described above map nicely to a version control model, both linear storage and graph-based storage.

Why can agents effectively use version control? Version control information is important, yet hidden from context until it’s needed. The version control model of recall is in the base model. No additional context is necessary to get an agent to use version control effectively. There’s a bug in the code. What changed since the last time this code worked? Consult version control and add that important piece of information to the context. This agentic memory model maps well to how humans use version control.

Can the version control model be extended to other pieces of context? Store and hide information until it’s needed. Provide a clear model to the agent for recall. Beads proves the answer to this question is yes.

Structured Data#

Beads shows that agentic memory needs schema, querying, and concurrency management, all features of the modern SQL database.

Tasks in Beads have explicit relationships enforced by traditional SQL database schema. This forces agents to read and write data in the correct structure. Agents work better with constraints, and databases provide explicit constraints on what data can be written.

Agents prefer structured data to selectively recall specific pieces of context. Agentic memory must be queried and filtered. In Beads, tasks are read via SQL queries. The queries can become moderately complex. To build relationships between tasks, joins are used.

In the multi-agent use case, many agents will be making writes to agentic memory. Concurrency must be managed. Databases have known transaction semantics that agents can easily navigate.

Dolt for Agentic Memory#

What is the only tool that provides true Git-style version control on structured data? It’s Dolt, the world’s first and only version-controlled SQL database. Dolt meets all the requirements of agentic memory.

Dolt is so perfect for agentic memory, Beads is migrating to Dolt. In Steve’s words:

The sqlite+jsonl backend is clearly me reaching for Dolt without knowing about it…Prolly Trees were clearly designed for exactly my kind of use case.

You can use Dolt as the Beads backend today by initializing Beads like so:

bd init --backend doltMoreover, Beads is the backend to Gas Town, Steve’s recently-released, multi-agent orchestrator. Gas Town shows that with the proper agentic memory, multi-agent systems are a reality.

Conclusion#

Agentic memory is here, and it’s powered by Dolt. Check it out by trying Beads. What else other than tasks should be stored in Dolt to make agents perform better? If you have any ideas, please pop by our Discord and let me know.