Dolt is a version-controlled relational database that serves as a drop-in replacement for MySQL. Starting from way back in 2021, we have been working to make Dolt go faster. Last week, we announced that Dolt officially matches MySQL’s performance on Sysbench.

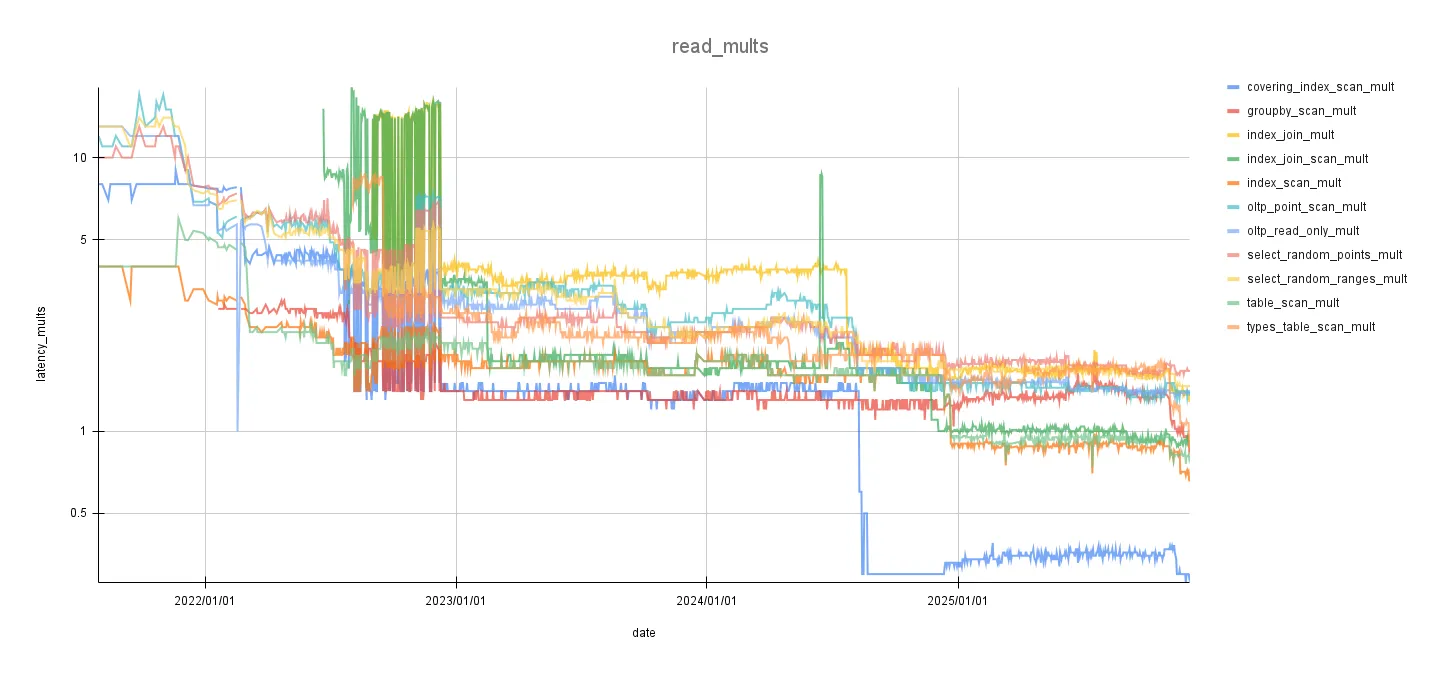

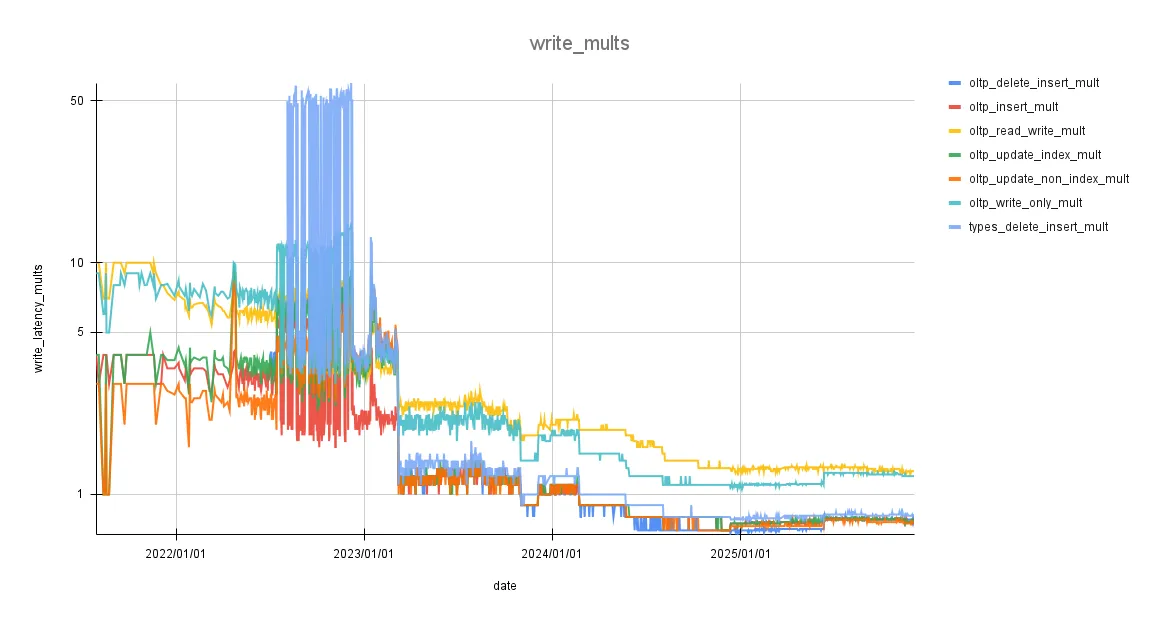

Here are some graphs of our latency improvements over various benchmarks:

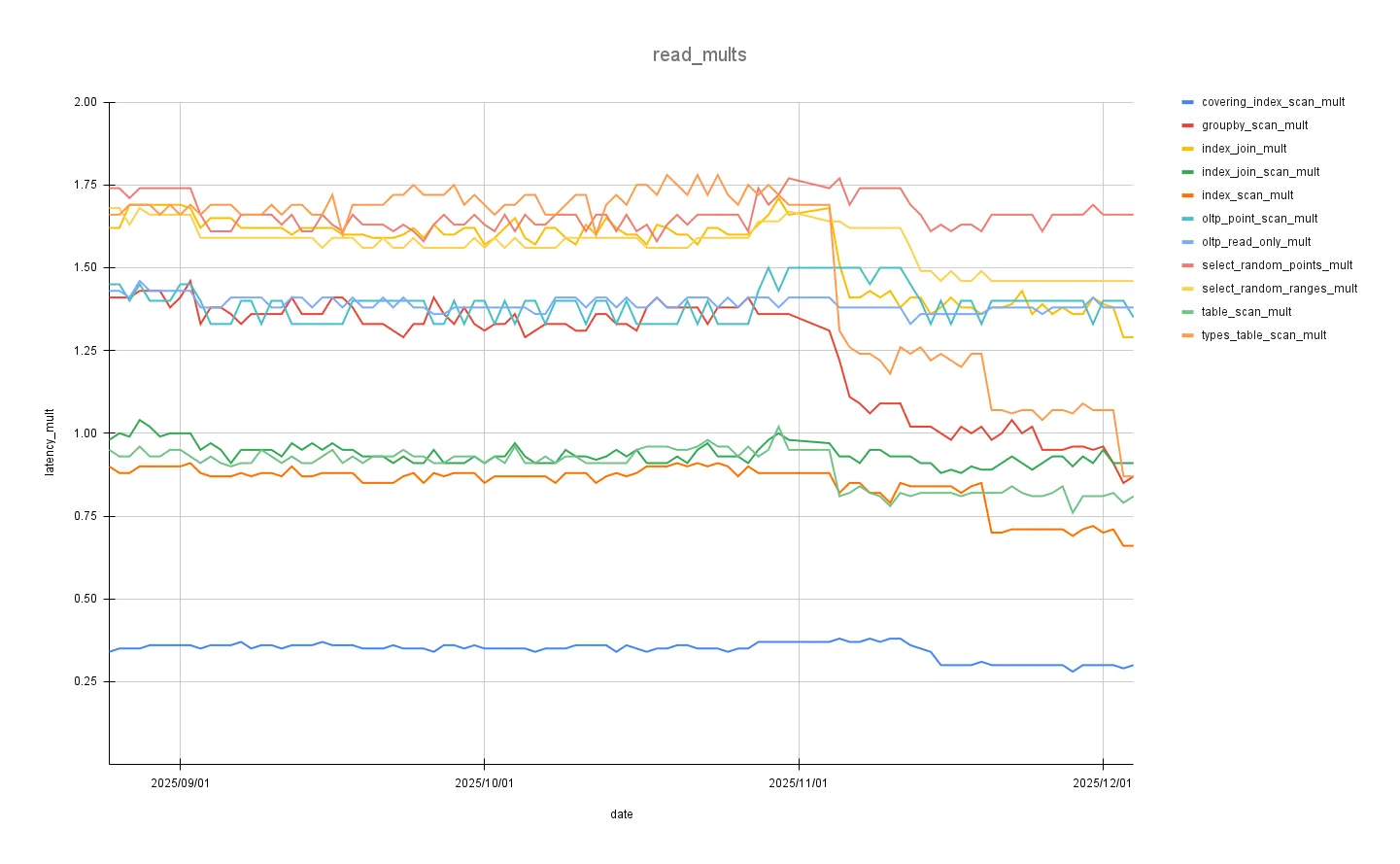

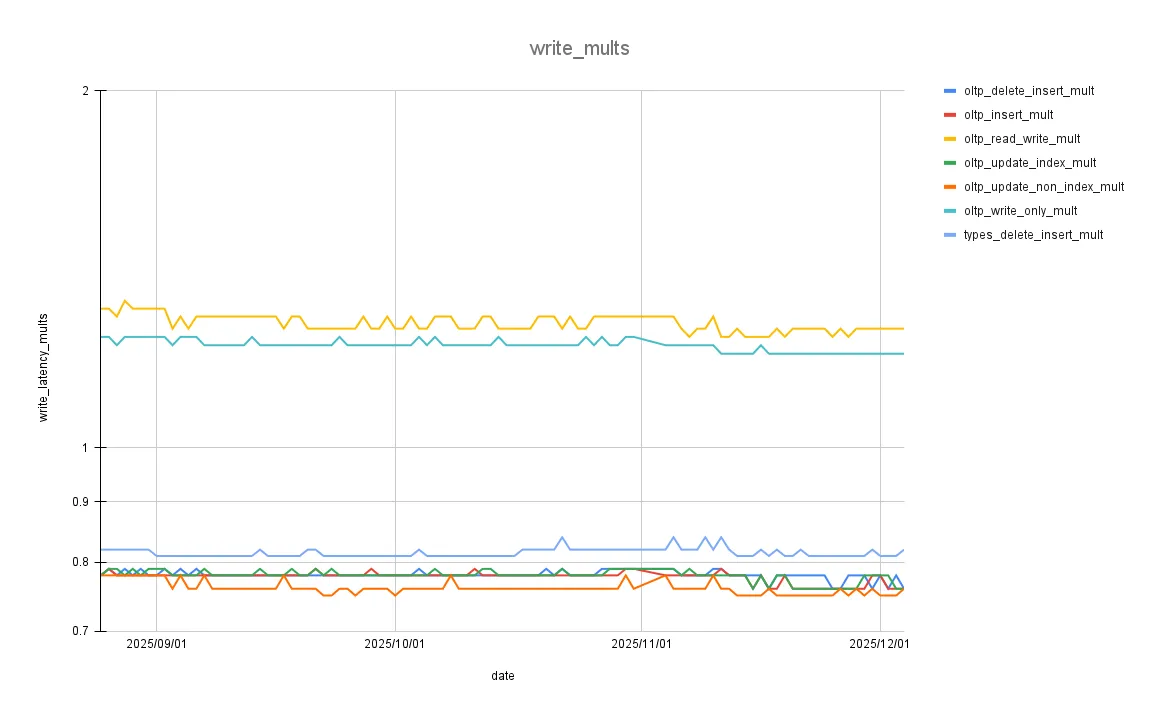

These are graphs zoomed-in to the changes covered in this blog:

The writes performance multiplier remains mostly flat, as the optimizations were focused almost entirely on improving read performance.

This blog will covert the recent performance improvements that finally pushed us over the edge.

Before these optimizations, our read_write_mean_multiplier was 1.16, meaning we were on average 16% slower than MySQL.

Field Align structs#

In Golang, fields in a struct are aligned based off their type (int64 takes up 8 bytes, bool takes up 1 byte, etc), and the compiler will insert padding where necessary.

For example:

type PoorlyAligned struct {

flag bool

count int64

id byte

}This struct will take up 24 bytes, because of the compiler will add padding after the bool flag.

We can reorder the declaration of these fields like so:

type WellAligned struct {

count int64

flag bool

id byte

}The resulting struct now only consumes 16 bytes.

This seems insignificant, but this padding can add up and make a measurable impact on performance and memory usage. You can read more about Struct Field Alignment here.

Fortunately, we don’t have to painstakingly realign every struct in our stack because the fieldalign linter exists.

Unfortunately, fieldalign’s -fix option deletes comments, so we had to manually bring those back across vitess, go-mysql-server, and dolt.

Overall, this brought our read_write_mean_multiplier down to 1.12.

A little tedious to incorporate, but it’s pretty much free performance.

ValueRow#

This next optimization involves implementing a new representation of our sql.Row type.

Currently, sql.Row is defined as []interface{} because rows of a table can contain a variety of types and interfaces{} are easy to use.

However, this comes at the cost of interface boxing.

When assigning values to an interface{}, Go will wrap concrete values in a hidden structure containing a type descriptor and pointer to the data.

Additionally, this data may escape to the heap.

You can read more about the details of Interface Boxing here.

When spooling results from the server out the client, we must convert rows into wire format, which is defined as a []Value.

type Value struct {

typ querypb.Type

val []byte

}In summary, we read concrete values from the Prolly Tree, box them in interfaces, do other stuff, and lastly convert them to wire format.

Seems obvious we should skip this boxing step and just have the rows in wire format to begin with.

Introducing sql.ValueRow:

type ValueRow []Value

type ValueBytes []byte

type Value struct {

Val ValueBytes

WrappedVal BytesWrapper

Typ query.Type

}This is actually not a novel idea for Dolt; we’ve had part of an implementation for this in our codebase since 2022 (lovingly named sql.Row2), but it was never fully implemented.

So, all we have to do is swap out sql.Row for sql.ValueRow.

Unfortunately, the “do other stuff” step makes this kinda hard.

dolt % grep -r "sql\.Row" | wc -l

5660

go-mysql-server % grep -r "sql\.Row" | wc -l

13648We’ve written a ton of logic that takes advantage of the flexibility of the interface{} type.

It’s just easier to perform more complicated conditional checks, math operations, string operations, etc with interfaces.

Fortunately, we don’t have to do this all at once.

Many database use cases are plain SELECT * queries that sometimes have a query.

The benchmarks index_scan, table_scan, and types_table_scan test exactly that.

After reviving sql.Row2 as sql.ValueRow and incorporating it for these code paths, our latency on those benchmarks all went down.

| benchmark | from_latency | to_latency | percent_change |

|---|---|---|---|

| index_scan | 30.26 | 29.19 | -3.54 |

| table_scan | 31.94 | 29.72 | -6.95 |

| types_table_scan | 130.13 | 99.33 | -23.67 |

Overall, this brought the read_write_multiplier down to 1.1.

It’s possible we expand this implementation to cover other queries, but for now, this is a start.

Duffcopy#

We’ve actually already talked about this next optimization in a previous blog.

In short, Golang is pass-by-value, meaning variables are copied when passed as an argument to functions.

During Prolly Tree traversal, we’re not passing val.TupleDesc and tree.Node as pointers, resulting in many unnecessary copies.

Relevant benchmarks after passing val.TupleDesc as pointers:

| benchmark | from_latency | to_latency | percent_change |

|---|---|---|---|

| covering_index_scan | 0.69 | 0.68 | -1.45 |

| groupby_scan | 18.61 | 17.01 | -8.6 |

| index_join | 2.57 | 2.35 | -8.56 |

| index_join_scan | 1.44 | 1.39 | -3.47 |

| index_scan | 29.19 | 28.16 | -3.53 |

| oltp_read_only | 5.37 | 5.28 | -1.68 |

| select_random_points | 0.64 | 0.62 | -3.13 |

| table_scan | 29.72 | 28.16 | -5.25 |

Relevant benchmarks after passing tree.Node as pointers:

| benchmark | from_latency | to_latency | percent_change |

|---|---|---|---|

| groupby_scan | 16.71 | 14.73 | -11.85 |

| index_join | 2.3 | 2.14 | -6.96 |

| index_join_scan | 1.39 | 1.37 | -1.44 |

| select_random_points | 0.62 | 0.61 | -1.61 |

| types_table_scan | 99.33 | 92.42 | -6.96 |

Overall, this brought the read_write_mean_multiplier down to 1.07.

Opt-in Branch Activity#

This optimization is another one we’ve already talked about before here. A few months ago, we added Branch Activity a feature to Dolt that helps users track how often and when a branch is read/written to. Unfortunately, this required adding logic onto hot code paths for dolt. As a result, we had to make this feature opt-in:

| benchmark | from_latency | to_latency | percent_change |

|---|---|---|---|

| covering_index_scan | 0.67 | 0.63 | -5.97 |

| groupby_scan | 13.95 | 13.7 | -1.79 |

| index_join | 2.14 | 2.07 | -3.27 |

| index_join_scan | 1.39 | 1.34 | -3.6 |

| index_scan | 29.19 | 28.67 | -1.78 |

| oltp_point_select | 0.3 | 0.28 | -6.67 |

| oltp_read_only | 5.28 | 5.18 | -1.89 |

| select_random_points | 0.61 | 0.58 | -4.92 |

| select_random_ranges | 0.61 | 0.57 | -6.56 |

| oltp_insert | 3.25 | 3.19 | -1.85 |

| oltp_read_write | 11.65 | 11.45 | -1.72 |

| oltp_update_index | 3.3 | 3.25 | -1.52 |

| oltp_update_non_index | 3.25 | 3.19 | -1.85 |

| types_delete_insert | 7.04 | 6.91 | -1.85 |

Overall, this brought the read_write_mean_multiplier down to 1.03.

Unsafe#

Dolt passes around data using protobuf messages with our ItemAccess struct to access slices of that data.

Here’s a piece of that code:

// GetItem returns the ith Item from the buffer.

func (acc ItemAccess) GetItem(i int, msg serial.Message) []byte {

buf := msg[acc.bufStart : acc.bufStart+acc.bufLen]

off := msg[acc.offStart : acc.offStart+acc.offLen]

if acc.offStart != 0 {

var stop, start uint32

switch acc.offsetSize {

case OFFSET_SIZE_16:

stop = uint32(val.ReadUint16(off[(i*2)+2 : (i*2)+4]))

start = uint32(val.ReadUint16(off[(i * 2) : (i*2)+2]))

// omitted

return buf[start:stop]Under the hood, Golang performs bounds checks when accessing members/sections of a slice.

Typically, the performance impact is negligible, and we don’t want to access parts of memory we’re not supposed to.

However, in a critical performance path, we can use the unsafe package and sacrifice some readability.

func (acc *ItemAccess) GetItem(i int, msg serial.Message) []byte {

bufStart := int(acc.bufStart)

if acc.offStart != 0 {

offStart := int(acc.offStart)

var stop, start uint32

switch acc.offsetSize {

case OFFSET_SIZE_16:

off := offStart + i*2

if off >= len(msg) || off+4 > len(msg) {

panic("attempt to access item out of range")

}

b3 := *(*byte)(unsafe.Pointer(uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(unsafe.SliceData(msg))) + uintptr(off+3)))

b2 := *(*byte)(unsafe.Pointer(uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(unsafe.SliceData(msg))) + uintptr(off+2)))

b1 := *(*byte)(unsafe.Pointer(uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(unsafe.SliceData(msg))) + uintptr(off+1)))

b0 := *(*byte)(unsafe.Pointer(uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(unsafe.SliceData(msg))) + uintptr(off)))

stop = uint32(b2) | (uint32(b3) << 8)

start = uint32(b0) | (uint32(b1) << 8)

// omitted

return msg[bufStart+int(start) : bufStart+int(stop)]Here, we manually check the bounds once before unsafely accessing the portions of msg that hold start and stop.

Additionally, we removed the intermediate off buffer and made this function a pointer receiver.

This yielded some nice perf:

| benchmark | from_latency | to_latency | percent_change |

|---|---|---|---|

| covering_index_scan | 0.64 | 0.55 | -14.06 |

Remember how Golang is pass-by-value?

This is especially bad when dealing with strings, as they can get quite large.

During serialization to wire format, there are places where we need to convert string to []byte.

Once again, this is where unsafe package comes to the rescue.

func StringToBytes(str string) []byte {

// Empty strings may not allocate a backing array, so we have to check first

if len(str) == 0 {

// It makes sense to return a non-nil empty byte slice since we're passing in a non-nil (although empty) string

return []byte{}

}

return (*[0x7fff0000]byte)(unsafe.Pointer((*reflect.StringHeader)(unsafe.Pointer(&str)).Data))[:len(str):len(str)]

}Using unsafe to cast a string to []byte is dangerous as it makes immutable strings mutable, but it’s fine here since the result of SQL() is immediately spooled to the client.

Performance from this change:

| benchmark | from_latency | to_latency | percent_change |

|---|---|---|---|

| index_scan | 28.67 | 27.66 | -3.52 |

| table_scan | 28.16 | 27.17 | -3.52 |

| types_table_scan | 92.42 | 90.78 | -1.77 |

Overall, this brought the read_write_mean_multiplier down to 1.02.

Balance goroutines#

During query execution and after analysis, there are two main steps the dolt server does.

The first goroutine calls rowIter.Next() in a loop, sending the results into a buffered channel

// Read rows off the row iterator and send them to the row channel.

var rowChan = make(chan sql.Row, 512)

eg.Go(func() (err error) {

defer close(rowChan)

for {

select {

default:

row, err := iter.Next(ctx)

if err == io.EOF {

return nil

}

if err != nil {

return err

}

select {

case rowChan <- row:

}

}

}

})The second goroutine drains rows from that channel, converts to wire format, then sends it to the client.

// Read rows from the channel, convert them to wire format,

// and call |callback| to give them to vitess.

var r *sqltypes.Result

eg.Go(func() (err error) {

for {

if r.RowsAffected == rowsBatch {

if err := resetCallback(r, more); err != nil {

return err

}

continue

}

select {

case row, ok := <-rowChan:

if !ok {

return nil

}

outputRow, err := RowToSQL(ctx, schema, row, projs, buf)

if err != nil {

return err

}

r.Rows = append(r.Rows, outputRow)

r.RowsAffected++Here, concurrency with buffered channels allows work to be done while waiting on long operations.

What if we added more concurrency?

The second step here can actually be split up; SQL() and callback() are both relatively costly operations.

Now, we have one goroutine in charge of serializing each row

// Drain rows from rowChan, convert to wire format, and send to resChan

var resChan = make(chan *sqltypes.Result, 4)

var res *sqltypes.Result

eg.Go(func() (err error) {

for {

select {

case row, ok := <-rowChan:

if !ok {

return nil

}

outRow, sqlErr := RowToSQL(ctx, schema, row, projs, buf)

if sqlErr != nil {

return sqlErr

}

res.Rows = append(res.Rows, outRow)

res.RowsAffected++

if res.RowsAffected == rowsBatch {

select {

case resChan <- res:

res = nil

}

}

}

}

)And another goroutine in charge of sending the results back to the client.

// Drain sqltypes.Result from resChan and call callback (send to client and potentially reset buffer)

var processedAtLeastOneBatch bool

eg.Go(func() (err error) {

for {

select {

case r, ok := <-resChan:

if !ok {

return nil

}

err = callback(r, more)

if err != nil {

return err

}

}

}

})These snippets have been trimmed for brevity; you can look through the full changes here.

Benchmarks from this change:

| benchmark | from_latency | to_latency | percent_change |

|---|---|---|---|

| covering_index_scan | 0.56 | 0.55 | -1.79 |

| groupby_scan | 13.95 | 13.7 | -1.79 |

| index_join_scan | 1.32 | 1.37 | 3.79 |

| index_scan | 28.67 | 25.28 | -11.82 |

| oltp_read_only | 5.18 | 5.28 | 1.93 |

| table_scan | 28.16 | 27.66 | -1.78 |

| types_table_scan | 92.42 | 81.48 | -11.84 |

There is a small performance hit on some benchmarks, as there is overhead when spinning up an extra goroutine and managing another channel, but it’s definitely worth it.

Overall, this brought the read_write_mean_multiplier down to 1.01.

Slices vs Arrays#

Dolt keeps a cache of materialized Prolly Tree nodes, to provide quick access for future queries.

type nodeCache struct {

stripes [numStripes]*stripe

}

func (c nodeCache) get(addr hash.Hash) (*Node, bool) {

// ...

}However, since all the methods for nodeCache are value receivers, Golang is actually performing a copy of the entire array every time.

Pass-by-value strikes again.

The fix is to just change nodeCache to be a slice instead:

type nodeCache []*stripeThis way, only the slice header is copied when calling nodeCache methods.

Resulting Benchmarks:

| benchmark | from_latency | to_latency | percent_change |

|---|---|---|---|

| groupby_scan | 13.22 | 11.87 | -10.21 |

| index_join | 2.07 | 1.96 | -5.31 |

| types_table_scan | 81.48 | 70.55 | -13.41 |

Overall, this brought the read_write_mean_multiplier down to 0.99.

Conclusion#

Dolt is a drop-in replacement for MySQL; you can get all the version control features with the same performance as MySQL. Dolt is a version-controlled database that performs (on average) just as well as MySQL on Sysbench. This doesn’t end here though; we can always go faster (sneak peek at a future optimization). Try out Dolt yourself, and feel free to file any performance issues. If you just want to chat, feel free to join our Discord.