We recently made changes in Dolt to support pushing databases to a Git remote. This makes it possible to push your Dolt database to remotes like GitHub, for example, so your version-controlled SQL database can use the same repository as your source code.

We built this feature to better support the transition of Beads and Gastown from SQLite to Dolt, by ensuring existing users of those tools could continue using their Git remotes to sync their data to, without having to provision new credentials for a traditional Dolt remote, like DoltHub or DoltLab.

I wrote the announcement blog last week which covers how to get up and running using a Git remote with a Dolt database, so check that out if you haven’t seen it yet. In today’s post I’ll do a technical deep dive into how we actually pulled this feature off.

A bit about remotes#

Before supporting Git remotes as Dolt remotes, Dolt supported three categories of remotes: filesystem based remotes, cloud-based remotes, and our full-service remote products DoltHub and DoltLab.

Filesystem remotes allow a location on disk to act as a Dolt remote. This means

that during a remote operation like dolt push, Dolt writes the database data

to this location on disk. When a remote read operation is performed, like dolt fetch,

remote data is read from this location on disk, back to the Dolt client.

Cloud-based remotes use cloud-based storage, typically an object or blob store, to persist Dolt remote database data. These function similarly to the filesystem-based remote, only the underlying storage is not a filesystem it’s an S3 bucket, for instance. These remotes also require users to supply cloud credentials and have the proper permissions to write and read from them. Currently, Dolt supports AWS, GCP, OCI, and Azure remotes.

DoltHub and DoltLab are our remote products. These are built atop the filesystem and cloud-based remote primitives, but add a suite of rich features on top of these implementations including a pull-request style workflow the way GitHub and GitLab do for Git repositories.

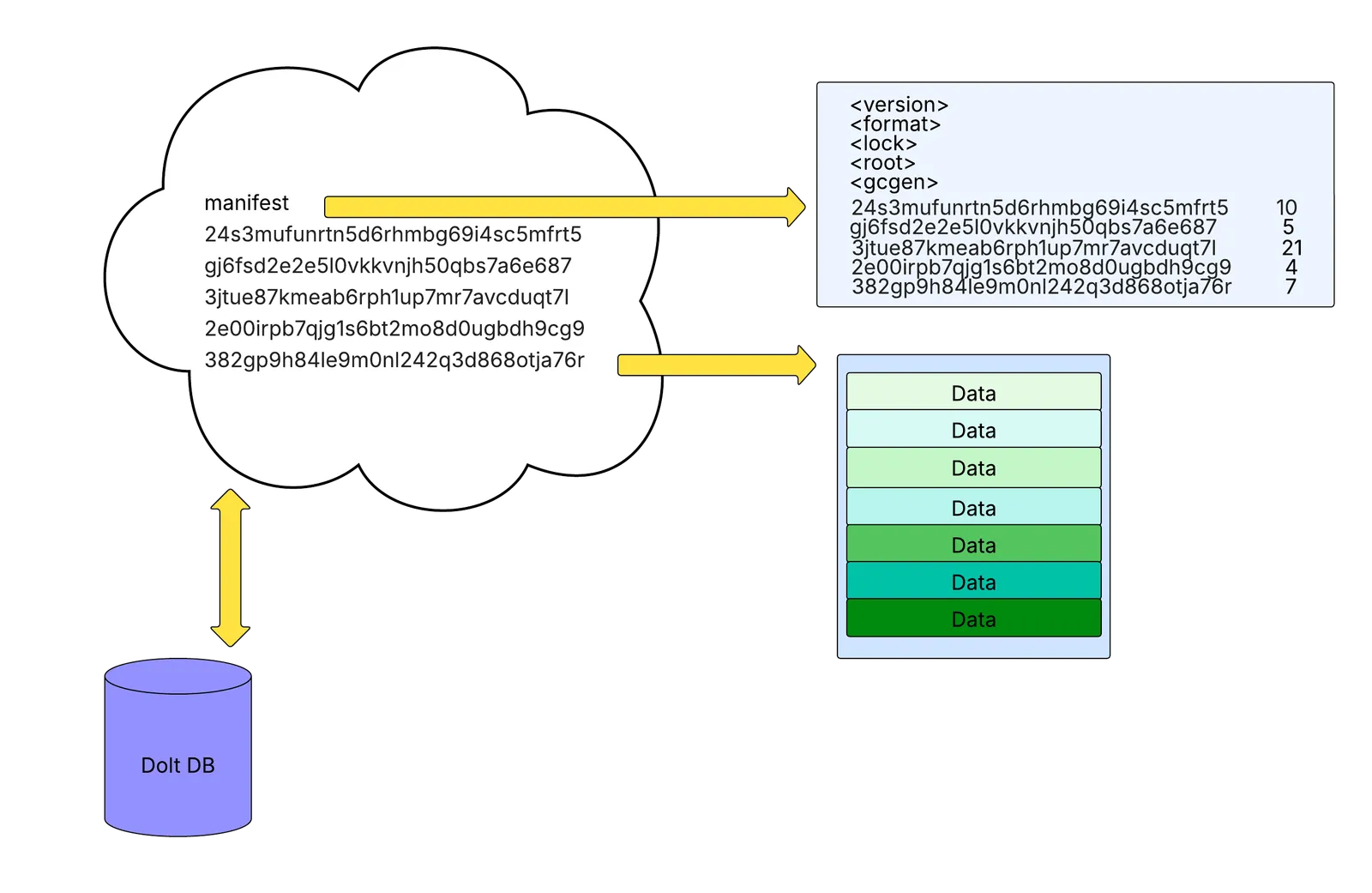

At a high-level, Dolt writes two types of files to a remote, an immutable tablefile which contains all database data for the history of the database, and the manifest, a mutable file that contains references to all relevant tablefiles, meaning those that contain all reachable database data. Some tablefiles may exist in remote storage which no longer contain reachable data. These are considered garbage and are safe to delete.

The diagram above shows how Dolt organizes data on a remote. The cloud represents remote storage containing the files as they might appear in cloud storage. The manifest file is shown along with a set of hash-named tablefiles. The arrows pointing from the manifest to the right show the manifest’s contents. Here you can see it contains important information like its version, storage format, lock hash, root hash, and garbage collection generation, along with references to each tablefile and their corresponding chunk count. The arrow pointing from the last tablefile to the right shows its contents which reveals the seven chunks of binary data it contains. The Dolt database below the cloud represents a Dolt client that pushes and pulls to this remote.

Fundamentally, a Dolt remote implementation needs to be able to accept writes or uploads of tablefiles and a manifest, it also must be able to serve or support downloads of these files entirely and at times in pieces, and it must support a compare-and-swap (CAS) write of files, which is crucial for writing the manifest in particular. The remote also needs to support concatenation of tablefiles since occasionally Dolt will “conjoin” data from multiple tablefiles into a much larger new one.

The common abstraction used to implement a new remote that covers all of these

requirements is the Blobstore abstraction in Dolt. It has the following methods:

type Blobstore interface {

Exists(ctx context.Context, key string) (ok bool, err error)

Get(ctx context.Context, key string, br BlobRange) (rc io.ReadCloser, size uint64, version string, err error)

Put(ctx context.Context, key string, totalSize int64, reader io.Reader) (version string, err error)

CheckAndPut(ctx context.Context, expectedVersion, key string, totalSize int64, reader io.Reader) (version string, err error)

Concatenate(ctx context.Context, key string, sources []string) (version string, err error)

}The methods listed above are pretty straightforward, they need to do exactly what

their name implies. Exists returns if a given key in the remote exists, where a

key is a manifest file or tablefile. Get returns the file contents as a whole,

or in pieces. Put writes a file to the remote. CheckAndPut performs a CAS write

to the remote, which is used to write the manifest specifically, and Concatenate

combines multiple files into a single one.

To support Git-backed Dolt remotes we wanted to use this same abstraction, which we know to be correct, but do so in a way that works with Git.

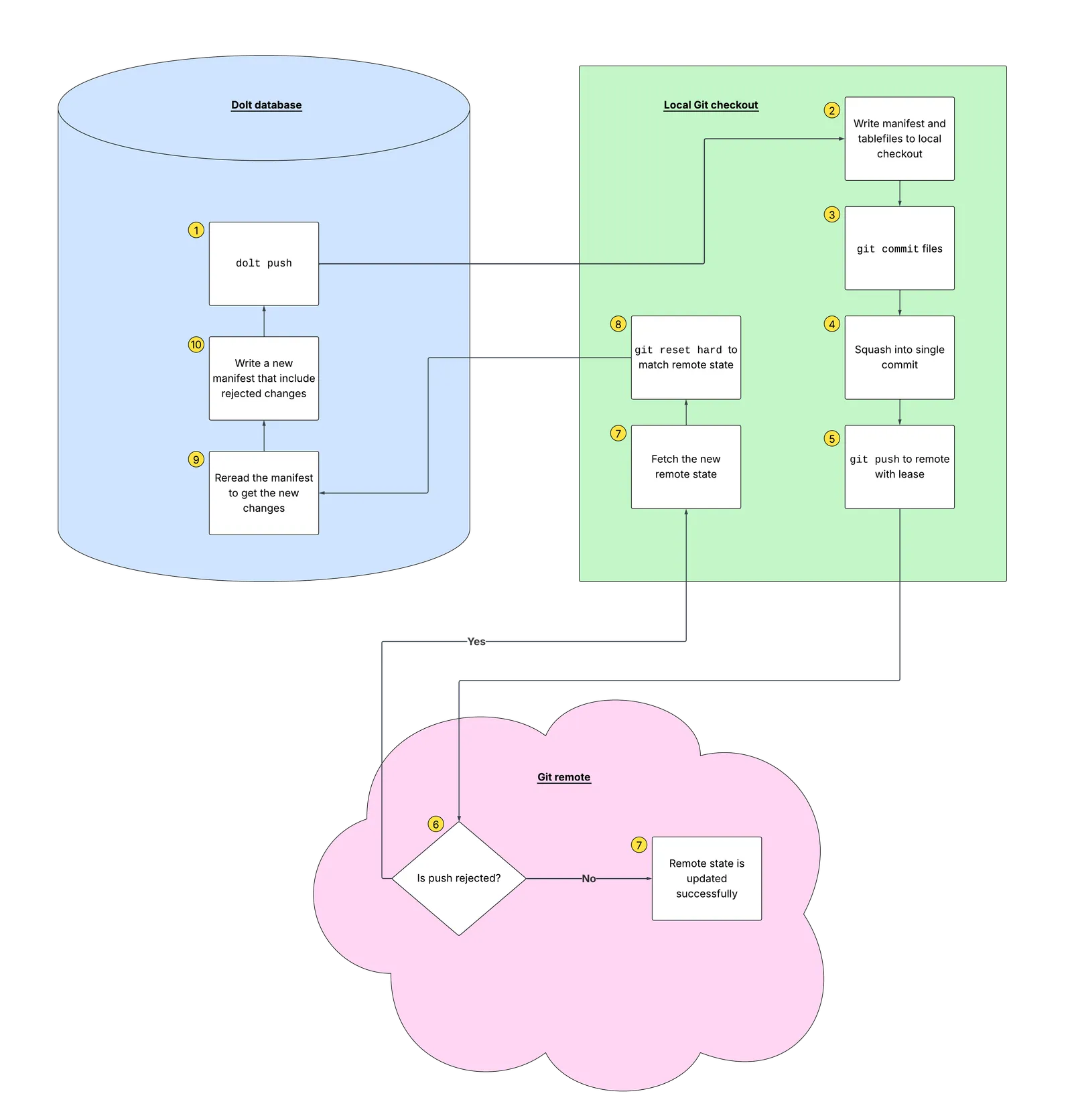

Initially when brainstorming a design for what components would be necessary for supporting Git remotes, we came up with a local Git-checkout based design.

In this design, there would need to be an existing remote Git repository, like on GitHub or GitLab, but crucially, this design would use local checkout of this remote repository that the Dolt client would use to facilitate its remote actions against the Git remote.

For example, a dolt clone in this design would first run git clone against the Git remote,

so that the remote repository was cloned locally and then Dolt would perform a

dolt clone operation behind the scenes against the local checkout,

as if it were a filesystem-based remote.

Similarly a dolt fetch would really be a git fetch and git checkout and

git reset --hard, to make the local checkout state exactly match the

Git remote state, then Dolt would perform a dolt fetch against the

local checkout as if it were a filesystem-based remote.

And it does not get any simpler for dolt push. In this world, first Dolt would

execute a dolt push to the local checkout, which would write to the working set and commit, then

it would run a git add ., then squash all changes into a single git commit,

then git push origin --force-with-lease.

If this git push succeeds, then the CAS was won, but if it did not, we’d need to

reset the local checkout to match the state of the remote again by fetching and resetting

from the Git remote, then rebase the Dolt changes against the new state of the

local checkout, and then retry the push again.

It became pretty clear to us that a big drawback of this design was that it

required complex handling of a local Git

checkout, which we also believed would fail under concurrency. Under a concurrent

workload, there is no way to guarantee that writes to the local

Git checkout would land atomically, especially in the case of a failed dolt push,

where we would need to reset and replay the writes.

It also wasn’t clear that this design fit the commonly used Blobstore abstraction,

which meant we’d need a new abstraction for these remotes, one that would need to

be independently verified as correct.

Fortunately, in the face of these challenges, we decided to consider a GitBlobstore

implementation of the Blobstore interface more seriously, which led us to an

investigation into how we could use Git’s internal commands to operate directly

on its underlying objects in order to correctly satisfy the Blobstore interface.

Fundamentally, Git stores four types of objects and exposes primitives to work with them directly. The object types are blobs, trees, commits, and tags. We’ll also be discussing Git refs a bit later, but those are not Git objects, they’re just pointers to commit objects. For our purposes we only care about blobs, trees, and commits (and refs).

Here is way too much information about Git internals and its plumbing commands.

Git internals#

A Git blob is raw contents of a file and Git hashes these contents to create the object ID of the blob. These IDs are the same, if file contents are the same, even if the files have different names.

# Store some content as a blob

$ echo "hello dolt" | git hash-object -w --stdin

012edb49e0a30a498e81c4f55e3762a009e1e049

# Verify it's a blob

$ git cat-file -t 012edb49e0a30a498e81c4f55e3762a009e1e049

blob

# Read it back

$ git cat-file blob 012edb49e0a30a498e81c4f55e3762a009e1e049

hello doltgit hash-object -w --stdin reads raw bytes from stdin, computes a SHA hash

of the content, writes the object into Git’s object store (that’s the -w

flag, without it Git would only print the hash without storing anything),

and prints the resulting object ID. Git’s content-addressable storage

guarantees that the same content always produces the same ID, no matter what you

name the file.

The next command we run is git cat-file -t <oid> which prints the type of the

object, which in this case is blob.

Lastly, git cat-file blob <oid> dumps the raw contents back out, where you

can see “hello dolt” again. hash-object and cat-file are plumbing commands

you can use to inspect any object in Git’s store.

Notice there’s no filename involved at this stage. hash-object just stores raw bytes and

returns an object ID. The filename-to-blob mapping is the job of a Git tree.

A Git tree is a directory listing. Each entry in a Git tree maps a filename to the object ID of either a blob or another tree (which is a subdirectory). Like blobs, trees are also content-addressed, meaning two directories with identical contents produce the same tree ID.

# Create a temporary index (so we don't touch the real one)

$ export GIT_INDEX_FILE=/tmp/dolt-index

# Start with an empty index

$ git read-tree --empty

# Add our blob to the index under the filename "hello_dolt.txt"

$ git update-index --add --cacheinfo 100644 \

012edb49e0a30a498e81c4f55e3762a009e1e049 hello_dolt.txt

# Write the index out as a tree object

$ git write-tree

ae461249f7f4b72aa653eae41d05ddaf0dd3c6cf

# Inspect the tree: it maps "hello_dolt.txt" to our blob

$ git ls-tree ae461249f7f4b72aa653eae41d05ddaf0dd3c6cf

100644 blob 012edb49e0a30a498e81c4f55e3762a009e1e049 hello_dolt.txt Git doesn’t let you create tree objects directly so we have to build them through an index file.

The index file in Git is a mutable, flat list of entries where each entry in the

file is a filepath, mode, blob object ID triplet. Interestingly, the index file is where

your working set changes are staged when you run git add. Once you want to

commit the changes in your working set, running git commit calls git write-tree

under-the-hood which produces an immutable tree object. Git then creates a commit

pointing to that tree object.

GIT_INDEX_FILE in the snippet above, points Git at a temporary file to use as

its index, then we run git read-tree --empty to initialize it. Next, git update-index --add --cacheinfo

registers our blob from earlier under the filename “hello_dolt.txt” with the standard file mode 100644.

At this point in time, the index file would contain the following:

$ git ls-files --stage

100644 012edb49e0a30a498e81c4f55e3762a009e1e049 0 hello_dolt.txt After this, git write-tree takes the index file and writes it to the object store

as a Git tree, returning the tree’s object ID. Finally, git ls-tree lets us inspect

the tree to confirm it contains the entry we expect.

If we had added a second blob to the index before calling write-tree, the

resulting tree would have two entries, like a directory containing two files.

The second object could have also been another tree, or a sub-tree. Sub-trees

work the same way as other tree entries do. This would just be an entry that

itself points to another Git tree. This is how nested directories are represented.

The next type of object is a Git commit, which is a snapshot of a Git tree, the root tree, which may contain subtrees. In addition to the root tree, the Git commit points to previous commits in the Git history (its parents). The first commit in a repository has no parents, and commits also contain metadata like author, timestamp, and message.

# Create a commit with no parent (first commit)

$ git commit-tree ae461249f7f4b72aa653eae41d05ddaf0dd3c6cf \

-m "add hello_dolt.txt"

8f3e42b1a47d9c05e6aa0be912b7085ff1c3d6e0In the snippet above we executed git commit-tree which takes the tree object ID

and a message and produces a commit object. Since this is the first commit,

it has no parent commits. If we later updated hello_dolt.txt, built a new tree, and

wanted to commit again, we’d pass the -p argument to link it to the previous commit

like so:

$ git commit-tree <new-tree-oid> \

-p 8f3e42b1a47d9c05e6aa0be912b7085ff1c3d6e0 \

-m "update hello_dolt.txt"These objects and commands form the full chain: blob → tree → commit. Each commit captures the complete state of the tree at that point, and the parent link forms the tree history.

Let’s quickly talk about Git refs, next, because they’re also an important element

we’d need for a Blobstore implementation.

A Git ref is a named pointer to a commit, which means it’s just a file on disk

that contains a commit’s object ID. Branches like main are also

refs, where refs/heads/main, or main for short, points to the latest commit

on that branch. Tags are refs too. As it happens, you can also create custom refs

under any path you want, and this is actually a feature of Git we explicitly took

advantage of in our GitBlobstore implementation.

# Point a ref at our commit

$ git update-ref refs/heads/main \

8f3e42b1a47d9c05e6aa0be912b7085ff1c3d6e0

# Read it back

$ git rev-parse refs/heads/main

8f3e42b1a47d9c05e6aa0be912b7085ff1c3d6e0In the snippet above, git update-ref creates or moves a ref to point at

the provided commit. Importantly, this command also supports an atomic

CAS mode where you can essentially say

“update this ref to new commit X, but only if it currently points

at old commit Y.” You would use this mode if someone else changed the ref out

from under you, so you fail the write atomically and can retry after that.

This command and its atomic mode were crucial for implementing safe concurrent

writes, as you’ll

see later on.

Git Refs are also what is pushed and pulled to a remote, when you run git push or

git fetch, for example. When these commands are run, they transfer Git objects

and update the corresponding refs on the remote.

Like the update-ref command, these remote commands support an atomic write mode.

You can use Git’s --force-with-lease flag to guarantee that your writes to the

remote either completely succeed or completely fail, like so:

# Fetch the current state of the remote ref

$ git fetch --no-tags origin +refs/heads/main:refs/remotes/origin/main

# Push, but only if the remote ref still matches what we fetched

$ git push --force-with-lease=refs/heads/main:<expected-oid> \

origin refs/heads/main:refs/heads/mainIf someone else pushed changes to our remote ref between our fetch and push,

--force-with-lease rejects our push attempt and we would have to retry.

This mode gives us the CAS semantics we used in the Blobstore.

Hopefully this breakdown gives you an idea for how we leveraged Git’s

internals to implement a GitBlobstore, a Blobstore whose methods

use these Git commands to implement the correct behavior we need for a remote.

One implication of using these Git primitives that may not be immediately clear is that it freed us from having to manage a local Git checkout the way we originally conceived to do.

Because we are working directly with Git objects, blobs, trees, commits, and Git refs, we don’t actually need a local checkout at all. Instead we can use a local Git bare repository.

A bare Git repository is a Git repository with no working tree, which means

it’s essentially just the contents of the .git directory, which is where

Git stores all objects, refs, and configuration.

In a normal Git repository there is the .git directory and the working tree,

which is the actual files on disk that you edit. Here, when you run git checkout,

Git reads blobs out of its object store and writes them as real files into the

working tree. This is great for human editing code, but for our purposes it’s unnecessary

overhead that would be too difficult to work with. The Blobstore never needs files on

disk, instead, it only needs to read and write Git objects directly.

If you’re curious you can create a bare Git repo by running git init --bare:

$ git init --bare /tmp/my-cache.git

Initialized empty Git repository in /tmp/my-cache.git/

$ ls /tmp/my-cache.git

HEAD config description hooks info objects refsAs you can see in the above output, there is no working tree, no checked-out files,

just the Git internals. This is what we decided to use for our GitBlobstore.

Putting it all together#

With these Git primitives we can map every Blobstore method to a Git plumbing

implementation.

To start, here are the key fields in a GitBlobstore instance:

type GitBlobstore struct {

gitDir string

maxPartSize uint64

remoteName string

remoteRef string

remoteTrackingRef string

localRef string

cacheHead git.OID

cacheObjects map[string]cachedGitObject

cacheChildren map[string][]git.TreeEntry

}The gitDir is the path to the bare Git repository we discussed above. We decided

to write these to Dolt’s data directory so each Dolt database will have its own

local bare repository, and clones on the same host will not clobber each other’s repo.

maxPartSize controls how large a single Git blob can be. Many Git hosting

providers enforce per-object size limit which our implementation needs to be

aware of and handle, since Dolt tablefiles can often be quite large. As I

mentioned earlier, Dolt also periodically conjoins multiple tablefiles into a single,

larger one, so we need to not do this in the GitBlobstore.

Our plan for the

implementation is to automatically chunk large Git blobs into multiple, smaller

blobs, stored under the key as a directory. For example, let’s say we encountered

a blob (tablefile) that was larger than maxPartSize, in our implementation,

instead of writing it as a blob, we want to write it as a

sub-tree (e.g. tablefile/0001, tablefile/0002, …)

where its children are blobs of the chunked tablefile. We would also reassemble these

transparently on read.

The remoteName is a named Git remote configured inside that bare repo,

pointing at the user’s actual Git remote URL, this is usually “origin”.

Below remoteName are three refs which is where things get really interesting.

Recall that it’s possible to create custom refs in Git. Unlike branches, custom refs are not automatically fetched, pulled, or cloned. They need to be retrieved explicitly. For this reason, we decided that it was best for Dolt’s remote data to live on a custom ref so that it never interferes with the normal usage and flow of the Git repository itself. Dolt could just manage the custom ref behind-the-scenes and users won’t even need to worry about it.

With this in mind, we added the remoteRef field to the GitBlobstore. This is

the single ref on the Git remote that will store all of Dolt’s data, essentially

turning the Git remote ref into object storage. Our implementation uses the custom

ref path, refs/dolt/data, so we don’t collide with normal branches or tags,

and the ref points to a Git commit whose tree contains the Dolt tablefiles and manifest

as Git blobs.

Next, the remoteTrackingRef is a local copy of the remote ref’s current state, updated

every time we fetch. It tells us “what did the remote look like the last

time we checked?”. Tracking the state of the remote ref is crucial for our GitBlobstore

since this is the value we pass with the --force-with-lease flag when pushing

the Git remote, in order to detect if there were concurrent changes on the remote

while this instance of the GitBlobstore was building a commit.

Then, localRef is a scratchpad where our GitBlobstore will write its changes

that need to be pushed to the remote. Importantly, this ref needs to be independent

of both the remote ref and unique to a Blobstore instance (so concurrent writers

don’t clobber the ref if they’re working on the same Git bare repository),

and of the remote tracking ref, which must always reflect the remote ref state.

When writing to the localRef, the GitBlobstore builds a new commit

(hashes the blobs, updates the index, writes a tree, commits the tree) and

then points localRef at this new commit. Then, it tries to push localRef to

remoteRef with a lease check against remoteTrackingRef. This architecture ensures

that if the push succeeds, it has won the CAS and everything is hunky-dory.

If the push fails, someone else pushed first and won the CAS, and this instance

must now fetch the new remote state, rebuild localRef on top of it, and retry

the push.

Both remoteTrackingRef and localRef include a UUID so that multiple

concurrent GitBlobstore instances sharing the same bare repo

don’t step on each other’s refs.

The last section of fields are related to the GitBlobstore’s internal

cache, which serves two very important purposes.

The first purpose is performance improvement. Every Blobstore read operation needs to know what’s

in the commit’s tree object, which means knowing what tablefiles

and manifest exist, what their object IDs are. Without a cache, we’d have

to run git ls-tree against the full tree on every Get and Exists call.

The second purpose is correctness under concurrency. When a GitBlobstore

instance loses a CAS race (another writer pushed to the remote first), it

has to fetch the new remote state and retry. At this point the remote’s tree

may contain tablefiles that weren’t there before, and without a cache, the

instance that failed the CAS would need to re-read the entire tree from

scratch before it could attempt a CAS retry. But in this case, because

tablefiles are immutable and thus once cached are guaranteed to be correct

and never stale, we can simply merge the new entries into the existing cache,

without invalidating and rebuilding the entire thing.

The only exception to this is the manifest, which is the only mutable file. The

manifest does need to be overwritten in the cache when it has changed.

To this effect, cacheHead tracks which commit object ID the cache was last built from.

When we fetch a new remote state, we compare the fetched commit to cacheHead

and if they match, there’s nothing to do. If they don’t match, we list the new commit’s

tree and merge its entries into the cache.

cacheObjects is a map from tree path (e.g. manifest, abc123def456...)

to the object’s ID and type. This lets us answer Exists and Get calls

by looking up the path directly in the cache without shelling out to Git.

Finally, cacheChildren maps a directory path to its immediate child entries. This

is needed for reading chunked tablefiles. We look up the children here to know

how many parts there are and read them in order.

With these fields in mind, here’s how each GitBlobstore method uses these

Git concepts and internals to actually make Git remotes work as Dolt remotes.

Exists#

Exists checks whether a key (a tablefile or manifest) is present on the

remote. Here’s the simplified logic:

func (gbs *GitBlobstore) Exists(ctx context.Context, key string) (bool, error) {

// Sync with the remote

err := gbs.syncForRead(ctx)

if err != nil {

return false, err

}

// Check the cache

_, ok := gbs.cache.get(key)

return ok, nil

}syncForRead does the heavy lifting here.

func (gbs *GitBlobstore) syncForRead() {

// Fetch the remote ref into our remote-tracking ref

git fetch --no-tags gbs.remoteName +gbs.remoteRef:gbs.remoteTrackingRef

// Resolve the remote-tracking ref to a commit OID

remoteHead = git rev-parse gbs.remoteTrackingRef

// Set our local ref to match (remote is source of truth for reads)

git update-ref gbs.localRef remoteHead

// Merge the commit's tree entries into the cache

if remoteHead != gbs.cacheHead {

entries = git ls-tree -r remoteHead

for each entry {

cache.mergeEntry(entry) // add if new, skip if exists

if entry is manifest {

cache.overwrite(entry) // manifest is always refreshed

}

}

gbs.cacheHead = remoteHead

}

}syncForRead fetches the latest state from the remote, then merges the

tree entries into the cache. After this, Exists is just a local map

lookup. If the remote ref doesn’t exist yet

the fetch returns “ref not found” and we treat the

store as empty, so Exists returns false for everything.

Get#

Get retrieves the contents of a key from the remote, supporting both

full reads and byte-range reads. Here’s the simplified logic:

func (gbs *GitBlobstore) Get(ctx context.Context, key string, br BlobRange) (io.ReadCloser, uint64, string, error) {

// Sync with the remote (same as Exists)

err := gbs.syncForRead(ctx)

if err != nil {

return nil, 0, "", err

}

// Look up the key in the cache

obj, ok := gbs.cache.get(key)

if !ok {

return nil, 0, "", NotFound{key}

}

// Read the data based on object type

switch obj.typ {

case blob:

// Key is a single blob, read it directly

size = git cat-file -s obj.oid

reader = git cat-file blob obj.oid

return sliceToRange(reader, size, br), size, obj.oid, nil

case tree:

// Key is a chunked sub-tree, read parts in order

parts = gbs.cache.children(key) // ["0001", "0002", ...]

reader = concatenatePartReaders(parts, br)

return reader, totalSize, obj.oid, nil

}

}Like Exists, Get starts with syncForRead to make sure the cache

is up to date. Then, it looks up the key in the cache. If found, the

behavior depends on whether the key is a blob or a tree.

If it’s a blob, the data was small enough to fit in a single Git object

based on maxPartSize, so we use git cat-file -s to get the size and

git cat-file blob to stream the contents. If the caller requested a byte

range (e.g. “give me bytes 1000–2000”), we slice the stream accordingly.

If it’s a tree, the data was chunked during a previous Put. We look up the

children from cacheChildren, open a reader for each part in order, and

concatenate them into a single stream, slicing to the requested byte range

if needed.

The version string returned from Get is the object ID, either the blob object ID or the

tree object ID. This is used later by CheckAndPut to detect concurrent changes.

Put#

Put writes a key to the remote. This is the most involved method because

it has to hash the data, build a new commit, and push it atomically. Here’s

the simplified logic:

func (gbs *GitBlobstore) Put(ctx context.Context, key string, totalSize int64, reader io.Reader) (string, error) {

// Sync to check if the key already exists

err := gbs.syncForRead(ctx)

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

// If the key already exists (tablefiles are immutable), skip the write

if key != "manifest" && gbs.cache.has(key) {

return existingVersion, nil

}

// Hash the data into blob(s) up front (so retries don't re-read the reader)

if totalSize <= gbs.maxPartSize {

blobOID = git hash-object -w --stdin < reader

plan = {writes: [{path: key, oid: blobOID}]}

} else {

// Chunk into parts

for each chunk of maxPartSize bytes from reader {

partOID = git hash-object -w --stdin < chunk

}

plan = {writes: [{path: key/0001, oid: partOID1}, {path: key/0002, oid: partOID2}, ...]}

}

// Push with CAS retry loop

gbs.remoteManagedWrite(ctx, key, plan)

}The exists check is an important optimization in this method. Since tablefiles

are content-addressed

and immutable, there’s no point writing one that already exists on the remote.

This avoids unnecessary writes during dolt push where many tablefiles

may already be present.

The hashing phase writes all the data into Git blob objects in the local bare repo

before attempting the push. This is important because the io.Reader can

only be read once, but if the push fails due to a CAS race we may need to

retry. By hashing up front, the blob OIDs are stored in the local object

store and can be reused across retries.

Last is the remoteManagedWrite loop, which is the core of the write

path:

func (gbs *GitBlobstore) remoteManagedWrite(ctx, key, plan) {

retry with exponential backoff {

// Fetch latest remote state

remoteHead, ok = gbs.fetchAlignAndMergeForWrite(ctx)

// Build a new commit on top of the remote head

if ok {

// Load the remote head's tree into a temporary index

git read-tree remoteHead -> tempIndex

} else {

// First write ever, start from an empty index

git read-tree --empty -> tempIndex

}

// Add our blob(s) to the index

for each write in plan {

git update-index --add --cacheinfo 100644 write.oid write.path

}

// Write tree and commit

treeOID = git write-tree (from tempIndex)

if ok {

commitOID = git commit-tree treeOID -p remoteHead -m "put <key>"

} else {

commitOID = git commit-tree treeOID -m "put <key>" // no parent for first commit

}

// Point our local ref at the new commit

git update-ref gbs.localRef commitOID

// Push with lease (this is the CAS)

git push --force-with-lease=gbs.remoteRef:remoteHead \

gbs.remoteName gbs.localRef:gbs.remoteRef

// If push fails (someone else pushed first), loop back to fetch

// If push succeeds, merge new commit into cache and return

}

}The retry loop is the heart of the concurrency model. Each iteration fetches

the latest remote state, builds a new commit on top of it, and attempts a

push with --force-with-lease. The lease check ensures the remote hasn’t

changed since we fetched. If it has, the push is rejected, we fetch again,

rebuild the commit on top of the new state, and retry. This is exactly the

compare-and-swap pattern the Blobstore interface requires.

CheckAndPut#

CheckAndPut is how the manifest gets written. It’s like Put, but with

an additional precondition where the write only succeeds if the key’s current

version matches an expected version. This is the application-level CAS

that sits on top of the Git-level --force-with-lease CAS.

func (gbs *GitBlobstore) CheckAndPut(ctx context.Context, expectedVersion, key string, totalSize int64, reader io.Reader) (string, error) {

var cachedPlan *putPlan

// CAS retry loop (same remoteManagedWrite as Put)

retry with exponential backoff {

// Fetch latest remote state

remoteHead, ok = gbs.fetchAlignAndMergeForWrite(ctx)

// Check the precondition: does the key's current version match?

actualVersion = ""

if ok {

obj, found := gbs.cache.get(key)

if found {

actualVersion = obj.oid

}

}

if expectedVersion != actualVersion {

return CheckAndPutError // version mismatch, stop, don't retry

}

// Hash the data (only on first attempt, reuse on retries)

if cachedPlan == nil {

cachedPlan = gbs.planPutWrites(ctx, key, totalSize, reader)

}

// Build a new commit on top of the remote head

// (same as Put: read-tree, update-index, write-tree, commit-tree)

commitOID = gbs.buildCommitForKeyWrite(ctx, remoteHead, ok, key, cachedPlan)

// Point our local ref at the new commit

git update-ref gbs.localRef commitOID

// Push with lease (this is the Git-level CAS)

git push --force-with-lease=gbs.remoteRef:remoteHead \

gbs.remoteName gbs.localRef:gbs.remoteRef

// If push fails, loop back to fetch and re-check version

// If push succeeds, merge new commit into cache and return

}

}The key difference from Put is the version check. Before building

a commit, CheckAndPut looks up the key’s current object ID in the cache

and compares it to expectedVersion. If they don’t match, it returns a

CheckAndPutError immediately. When this happens, no push is attempted, and no retry happens.

This is how Dolt ensures that manifest updates are serialized. A writer first reads

the manifest, computes a new one, and writes it back with CheckAndPut

using the version it originally read. If another writer updated the

manifest in between, the versions won’t match and the write fails.

Concatenate#

Concatenate combines multiple existing keys (source blobs) into a single

new key. Dolt uses this to “conjoin” small tablefiles into a larger one.

func (gbs *GitBlobstore) Concatenate(ctx context.Context, key string, sources []string) (string, error) {

// Sync with the remote

err := gbs.syncForRead(ctx)

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

// If the destination key already exists, skip (same as Put)

if key != "manifest" && gbs.cache.has(key) {

return existingVersion, nil

}

// Read each source blob and concatenate into a single stream

totalSize = sum of sizes of all sources

reader = concatenatedReader(sources) // streams source blobs in order

// Hash the concatenated data into blob(s)

plan = gbs.planPutWrites(ctx, key, totalSize, reader)

// Push with CAS retry loop (same as Put)

return gbs.remoteManagedWrite(ctx, key, plan)

}Concatenate is straightforward once you understand Put. It reads the

source blobs from the local object store (they were already fetched during

syncForRead), concatenates them into a single stream, and then follows

the exact same write path as Put.

Conclusion#

And there you have it, a GitBlobstore implementation that turns any Git

remote into a Dolt remote using nothing but Git plumbing commands and a

local bare repository!

Though it was the major piece of engineering that made Git remotes

as Dolt remotes possible, the GitBlobstore doesn’t work totally alone.

It actually plugs into Dolt’s Noms Block Store (NBS) layer, which is the

same storage engine that powers all other Dolt remotes.

NBS handles the higher-level concerns like reading and

writing the manifest, coordinating tablefile uploads, and triggering

conjoins at the right time, while the Blobstore underneath handles the actual storage.

By implementing the Blobstore interface, the GitBlobstore slots in

seamlessly to NBS, so it doesn’t know and doesn’t have to care that it’s talking to a Git remote

instead of S3 or a local filesystem.

We hope you enjoyed this dive into our latest feature. If you’re excited about Git remotes, or want to talk about Dolt and how you can start building with it, come by our Discord, we’d love to meet you.