Here at DoltHub, we built the world’s first and only version-controlled SQL database, Dolt. We’ve written a lot about how we built Dolt but we’ve never discussed alternative architectures.

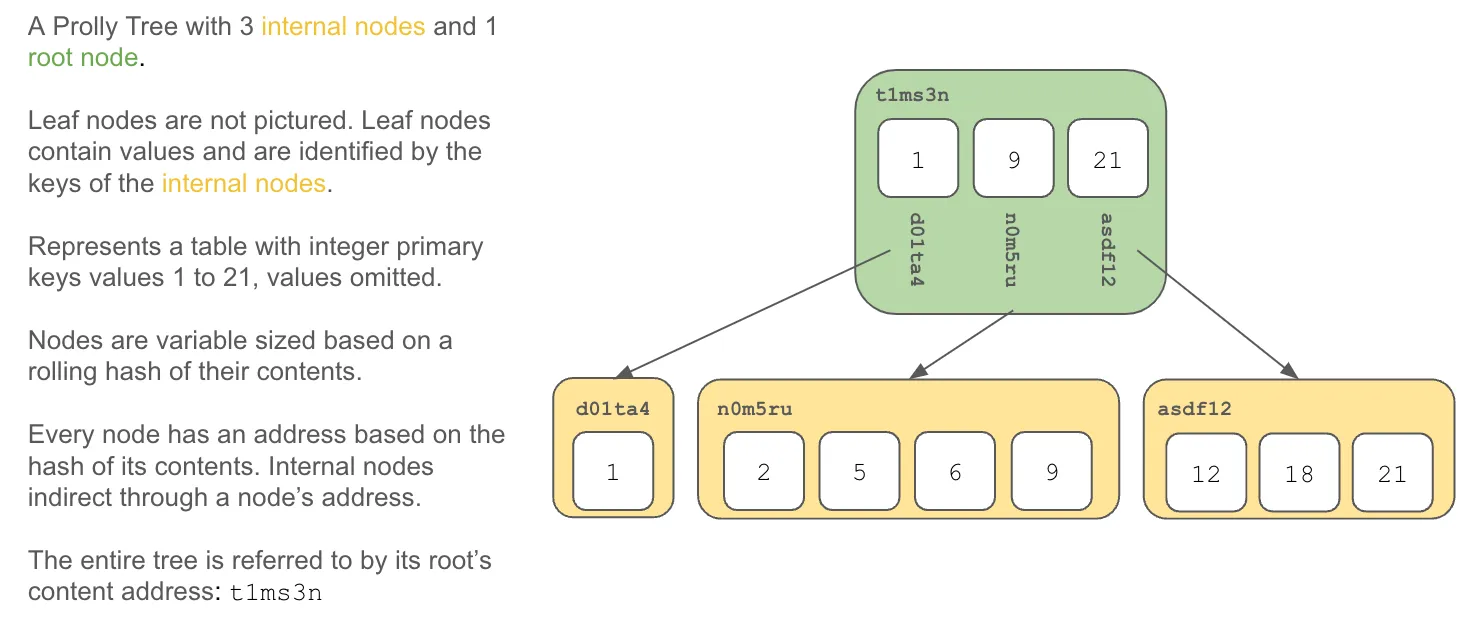

Dolt is built on top of a novel data structure called a Prolly Tree that was invented by the good folks who built Noms. We think that’s the best way to bring version control to databases but there are other ways. This article discusses the design space.

Requirements#

What makes a database a database? What makes version control version control? What are the essential characteristics of a version-controlled database?

When discussing version control, the set of features I envision are long-lived branches, granular diffs, merges with conflict resolution, and a historical log of changes back to inception. Multi-version Concurrency Control (MVCC) (ie. transactions) in databases only provides branched writes and rollback on conflict. This is not version control. Version control approximates all the features of Git, the most popular version control system, on tables or collections instead of files.

Can’t you just use Git as a database? Just add a few comma separated value (CSV) or Javascript Serialized Object Notation (JSON) files to your Git repository? Or even better, just put your SQLite file in a Git repository?

Let’s start with requirements to show why these solutions are not a version-controlled database.

Scale and Performance#

Databases store large collections of structured data. Git versions text files. Databases also store data as files on disk. However, these files are not human-readable text files. In order to scale to large collections of data, databases implement a number of optimizations rendering the files they store on disk unreadable as text. Optimizations include compression to preserve disk space and structuring data in search trees for fast seek, insert, update, and delete.

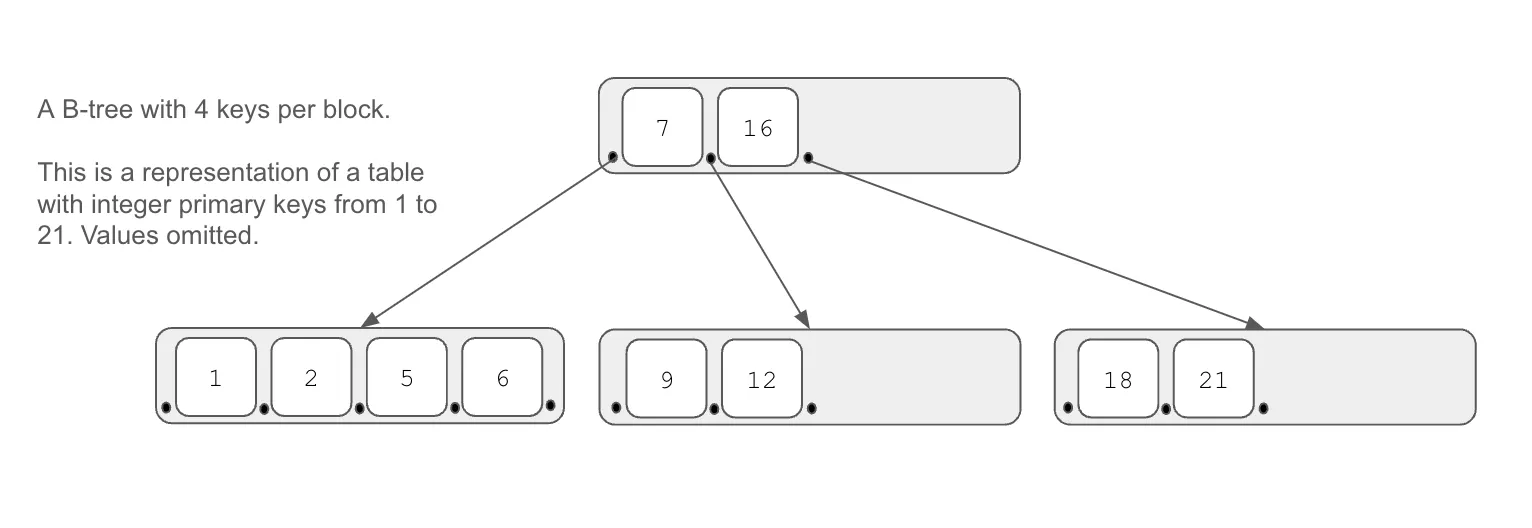

Search trees form the backbone of most database storage. Search trees provide log(n) seek, insert, update, and delete performance where n is the number of records in the database. log(n) performance means databases can perform operations quickly for even very large databases. Common search trees are Binary Trees, B-trees and (a,b)-trees. Most common open source SQL databases like SQLite, MySQL, and Postgres are built on B-tree-based storage engines.

Moreover, since databases are intended to store large collections of data, an expressive query language is needed so the database can only retrieve the portion of the data the user needs. Database query engines are complex. These query engines ensure database performance at scale for as many user queries as possible.

Fast, Granular Diff#

Version control systems allow a user to store, compare, and merge many versions of a record. In most version control systems, the record is a file. The version control system presents to the user which files have changed. The version control system can produce granular, line-based diffs for particular changed files quickly. If a user merges two versions of a file together, the two versions are combined as long as there have been no conflicting line edits. The ability to produce granular diffs between versions is essential to version control.

In a version-controlled database, the ideal record is a row or document. A table or collection can be millions of rows or documents. If the version control system reports a table has changed, has a single row or all million rows changed? A user wants to inspect the row- or document-based differences between two versions. If the user wants to merge two versions together, conflicts should be calculated on the basis or rows or documents.

Unfortunately, calculating the difference between search trees, the backing store for tables or collections, is an nlog(n) operation. You must iterate through one search tree and lookup whether the value exists in the other. This will be very slow for large tables. Building a search tree that can be compared to another search tree in a worst case time of log(n) or faster is a key challenge for version-controlled databases.

Structural Sharing#

Since databases are large, it is untenable to store many versions of a database if versions are stored as copies. Databases can be gigabytes or terabytes so storing even dozens of copies will become very expensive especially combined with the need to retrieve data quickly. Thus, a version-controlled database must share storage between versions. Sharing storage between versions is called structural sharing in version control parlance.

Database Storage Architecture#

Dramatically simplifying a very complex topic, database storage is built using a combination of search trees and pages. Search trees structure the data for fast seek, insert, update, and delete. Pages are the unit of that search tree that is written to disk. These two concepts have version control implications.

Search Trees#

Databases are built on search trees with the most common variant being B-trees. Different databases use different search tree architectures. A common architecture for tables or collections is to store data as key-value maps with keys stored in a search tree. The values of the row dangle off the bottom of the leaf nodes of the tree. In SQL databases, primary keys are used to identify a row and are required to be unique. Similarly, indexes are structured as a map of value to key and stored in a search tree, providing fast lookup of the key by value.

Notably, Postgres uses a slightly different table storage architecture. Postgres stores table data in a heap, instead of directly in a search tree, with indexes to the heap stored as search trees.

One consequence of this architecture as it relates to version control is that insertion order matters. The internal structure of the search tree depends on the sequence of queries you used to create the data. This means that you cannot examine storage to compute the difference between two table versions. You must iterate through one search tree and lookup the value in the other to compute the difference, an nlog(n) operation.

Another note from a version control perspective is that changes to a search tree can sometimes result in a bulk restructuring of the tree. Most search trees require node splitting and rebalancing, which edit many of the internal nodes of the tree. This makes structural sharing across versions difficult.

Pages#

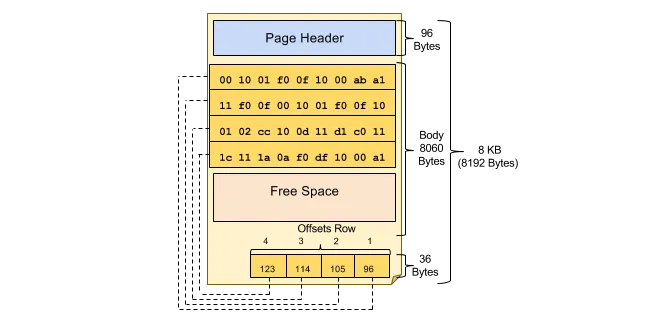

Once the data in your database is laid out in a search tree, it must be written to disk. The B-tree is broken down, or chunked in database parlance, into fixed sized pages. Pages are given addresses for fast lookup and retrieval. These pages are then grouped and written to disk as files. Pages are designed to fit into memory pages maintained by your operating system.

From a version control perspective, the atomic unit of change to a database is a page. If you want to store every version of a database, you are going to be storing database pages. Database pages are usually 4KB. A version control system would ideally store pages that changed and no more.

Version Control Approaches#

Now, let’s discuss two common version control approaches:

- Checkpoints and Patches

- Content-Addressing

Checkpoints and Patches#

The checkpoint and patch approach to version control tracks changes to files over time by storing checkpoints or snapshots and the differences between checkpoints called patches, deltas, or diffs. This technique is employed in older file version control systems like CVS, Subversion, and Perforce.

In a simple implementation, the latest version is stored in a full checkpoint, and patches are stored all the way back to the original state of the files. This is the most space-efficient solution. The latest version is the most likely to be accessed by the user, so logically, it should be the fastest to retrieve. Conversely, the oldest version will be the slowest to retrieve because all the patches must be applied to compute it.

With additional checkpoints you can trade space for faster computation of a version. The version control system can trigger a checkpoint on important operations like branch creation. Branches in a checkpoint-and-patch system are heavyweight and thus somewhat limited.

Diffs between versions close in history can be calculated quickly. Indeed, a diff between two subsequent versions is stored as a patch. Thus, the further the distance between versions in history, the longer the diff takes to calculate. Moreover, the inverse diff is often easily computed. Additions become subtractions and vice versa. Thus, you only ever have to apply a maximum of n/2 diffs where n is the number of differences between snapshots.

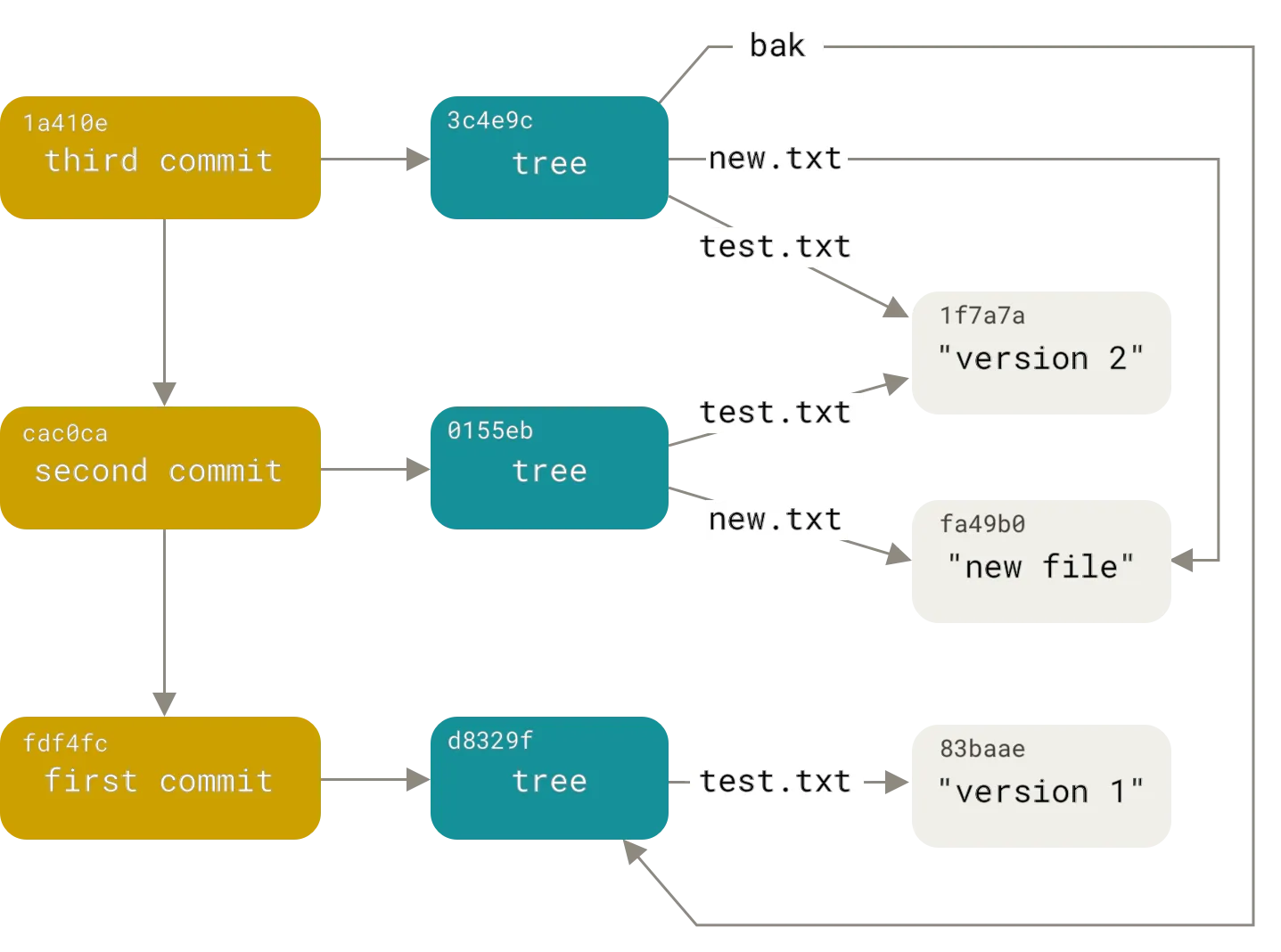

Content-Addressing#

The content-addressing approach to version control consists of only checkpoints. To achieve fast diff and structural sharing, each file is given a content address. A content address is a strong hash of the files contents. Thus, files with the same content address are the same and only stored once. This process is recursive with the directories stored in version control. Directories are given content addresses calculated using the content addresses of the files and directories they contain. This process is repeated up to the root of the version-controlled directory. The root hash is then stored in a graph of versions to provide history and branching functionality. Git and Mercurial use this technique.

Fast difference computation is delivered via content-addressing. If the root content address is the same, all the files in the tree are necessarily the same. If the root content address is different, go to the next layer of content addresses ignoring the addresses that are the same. Recursively, perform this computation until you get to the bottom of the tree. This approach allows diffs to be computed in time on the order of the differences. Unlike checkpoint-and-patch, content-addressing offers fast diff computation even in the case where the distance between versions is large. This feature is one of the reasons Git became the most popular version control system.

For the content-addressing approach to version control to work, history independence must be preserved. The order in which you create, delete or edit files must result in the same content address. By using the content of a file or directory as the basis for the address, history independence is achieved.

Potential Implementations#

With a basic understanding of version-controlled database requirements, database storage implementations, and version control approaches, version-controlled database implementations start to take shape. Which version control approach works better for databases?

Snapshot and Log#

In databases, a common backup strategy is to perform a snapshot either using a disk-based utility or a dumping utility. Then, a log of all writes is preserved from the point of the snapshot. Could a similar approach be used to provide version control in addition to backups? Would preserving all snapshots and all write logs give you a version-controlled database?

The first problem with this naive approach is the lack of structural sharing. Each snapshot will not share storage with other snapshots. The write log grows unbounded with the number of changes. Neon provides limited version control using a copy-on-write filesystem for snapshotting. The filesystem provides structural sharing as long as the files on the filesystem remain unchanged. Practically, this means storage is shared until a search tree must node split or rebalance. These operations change many database pages at once.

The second problem with this approach is diff computation. The write log necessarily contains the write queries or point edits between the snapshot and the current database. However, assembling any version between the snapshot and current requires applying those writes to a snapshot. Applying these writes is more computationally expensive than in the file case and requires an additional copy of the database. Moreover, the write log is not history independent. To know two different write histories resulted in the same database requires full computation and then comparison of the two resulting databases. This makes merging untenable with this approach. Neon does not provide diffs or merges.

The combination of these two issues means the snapshot and log approach fails to provide adequate structural sharing and fast, granular diffs, two of the three requirements of a version-controlled database.

Prolly Trees#

What if there were a content-addressed search tree? Could you store data and indexes in that search tree to create a Git-inspired version-controlled database? When combined with a content-addressed store of database pages would structural sharing of data be achieved?

The good folks at Noms invented a content-addressed B-tree they called a Prolly Tree. This data structure forms the basis of the world’s first and most complete version-controlled database, Dolt.

The documentation on Prolly Trees goes into vivid detail on how Prolly Trees are constructed, how they provide history independence and fast diff, and how table data is structured as Prolly Trees in Dolt. Dolt provides Git-style version control at database scale and performance.

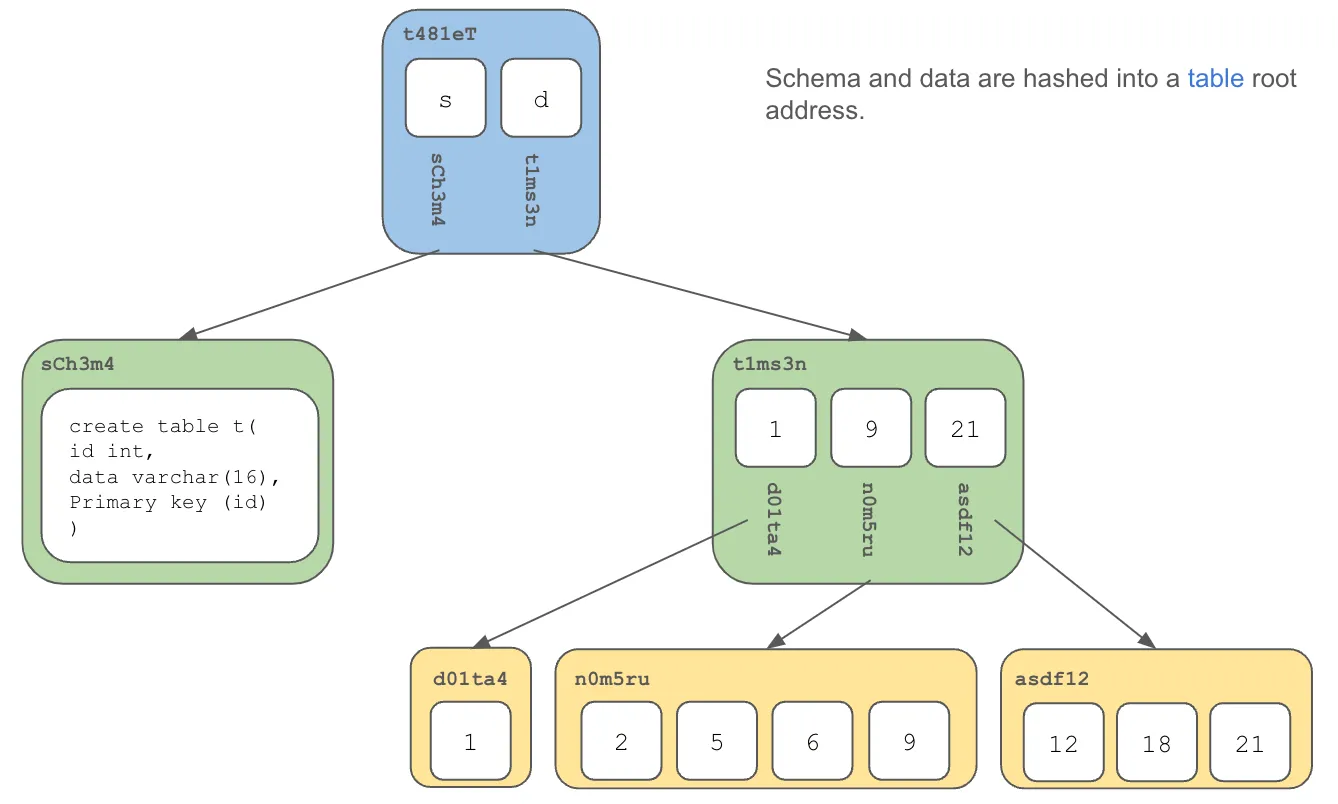

Table data is stored in a Prolly Tree. Each table version has an immutable content address of the data in the table. In SQL, tables also have schema. Table schema is stored in a much simpler Prolly Tree and given a content address. The combination of the roots of the schema and data Prolly Trees form the content address of the table.

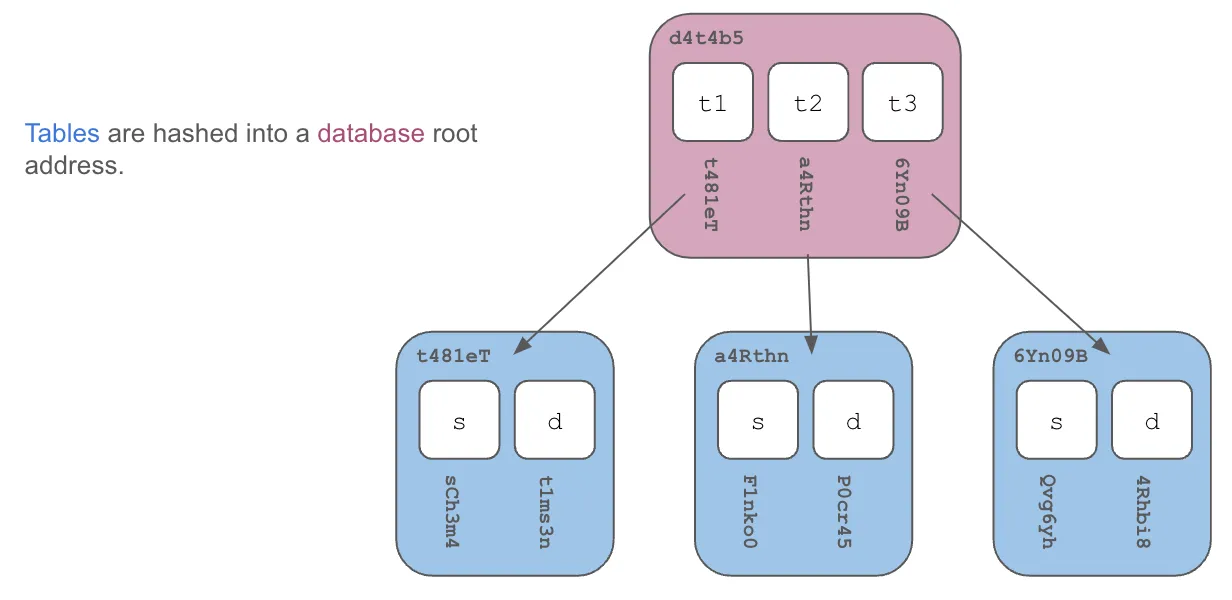

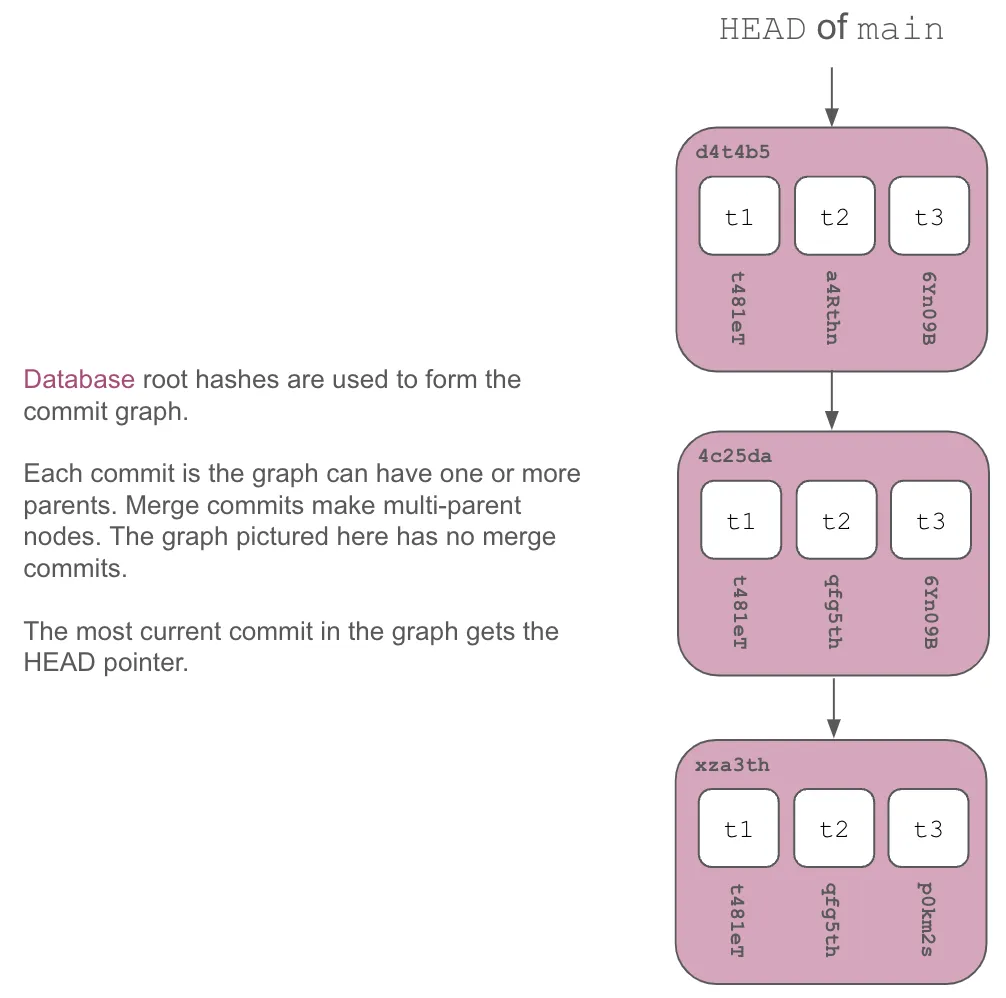

Tables are hashed along with any other versioned database objects into the database content address.

These roots are then laid out in a commit graph of versions, much like Git.

Conclusion#

Prolly Trees are the only viable way to provide database version control. Dolt is working proof. Questions? Come by our Discord and ask.